Luxury housing is increasing in Miami. So is homelessness.

Every night in Miami, nearly 4,000 people don’t have a home to sleep in.

Miami-Dade County leads the state of Florida in homelessness, a problem experts attribute to a scarcity of affordable-housing. In comparison to the 3,721 total homeless reported in Miami-Dade County, nearby Hillsborough County, which includes the city of Tampa, reported 1,549 homeless in 2017. Broward County, which includes Ft. Lauderdale, reported 2,450.

Over the last five years, home values and rent prices have skyrocketed in Miami, pushing more people out of their homes. Between 2013 and 2016, the area saw the steepest increase in home values in a decade. It also saw a stark increase in homelessness.

The homeless population in Miami-Dade County increased by 11.4 percent over that same period, while the number of homeless people in other Florida counties decreased.

A lack of affordable housing is the largest factor contributing to homelessness in Miami, said Evian White De Leon, program and policy director for Miami Homes For All, a charitable coalition that funds initiatives, conferences and educational efforts to solve problems related to homelessness.

“The affordable housing is the big piece. That is really the overarching cloud of this all because even if you were to build all the shelters in the world to house folks who are on the street homeless right now … the question is what next?” De Leon said. “If they can’t afford the rent and they cant afford to live where they work and where their kids go to school, I find it really hard to think of a bigger barrier to pushing homelessness aside or eradicating homelessness.”

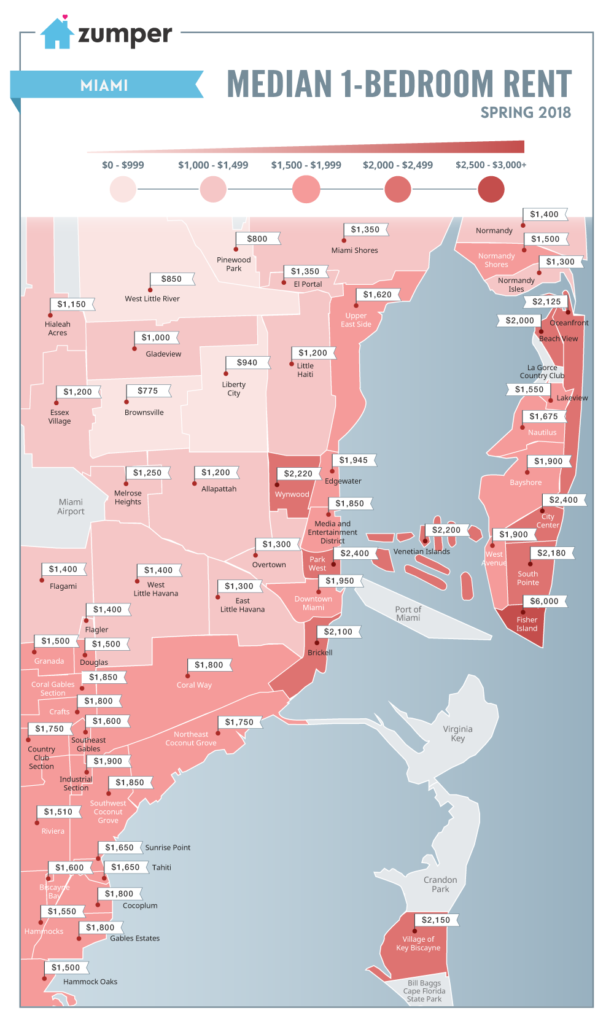

Since 2010, the Miami-Ft. Lauderdale-West Palm Beach metro area has approved more than 120,000 new building permits for housing. Most are being used to build luxury condominiums and skyscrapers in areas like Brickell, where rent averages around $2,100 for a one-bedroom apartment.

Meanwhile, affordable housing has taken a backseat. In 2011, the city of Miami Beach vowed to build 16,000 affordable-housing units for low- and middle-income people by 2020, but is not on track to meet that goal.

Home Value Index

Data Provided by Zillow Group

The city of Miami did not respond to several phone calls and emails regarding the connection between affordable housing and homelessness or the city’s strategy for affordable housing.

Earlier this year, City Manager Jimmy Morales wrote a letter to the Miami Beach Commission explaining that while more than 5,000 families applied for affordable housing in 2015, just 462 were placed into actual homes. For three years, 532 families have remained on the waitlist.

Last year, Miami-Dade County created the Workforce Housing Development Program as a way to incentivize developers to build affordable housing for families whose incomes are within the range of $42,600 to $99,400 for a family of four.

But getting for-profit developers to build affordable housing can be difficult since they are essentially being asked to build something that won’t reap any financial gain, De Leon said.

“Not sure how you could ask a developer to build something where they know they’re going to take a loss. It’s just no business works that way,” De Leon said. “It’s very complex, unfortunately it’s not just the story of well, the government said they were going to put forth X number of units and it didn’t happen, like, shame on them. It’s a much bigger issue, from the ground up and the top down.”

The market forces these new luxury units have on median rent and overall affordability in Miami could also be a large factor in increasing homelessness, said Thomas Byrne, assistant professor in the Social Welfare Policy department at Boston University.

“Luxury housing kind of puts upward pressure on median rent or median levels or market rent in the community … and one of the things that we see is that communities with higher rent levels tend to have higher rates of homelessness on average,” Byrne said.

Property values have steadily increased in Miami since the depths of the Great Recession. This past year alone, prices have risen 7.5 percent, according to the Zillow Group. While increasing property values are positive for anyone looking to sell in the market, it also further limits who can afford to buy.

That’s because despite increasing property values, wages have barely budged.

In Miami, the median household income in 2013 was $31,070. According to the most recently available data, it had grown only modestly by 2016 — to $34,901. A 12 percent change over three years.

Demographia International, a team of London School of Economics Professors who rate housing affordability markets around the world, ranked Miami as one of the most unaffordable housing markets in the world in its 14th annual international housing affordability survey last year.

Renters by Income and Cost Burden (Florida 2015)

A bar chart, Renters by Income and Cost Burden (Florida 2015), built by anonymous using ChartBlocks.

According to Elizabeth Bowen, assistant professor of social work at the University at Buffalo School of Social Work, this pattern of increasing rent and unaffordability can be seen in other cities across the United States, too.

“Generally housing is getting more and more unaffordable for more people … ,” Bowen said. “There is basically no part of the United States where a two-bedroom apartment would be affordable for somebody working full time at minimum wage.”

In fact, as noted in the 2017 Home Matters report by the Florida Housing Coalition, nearly one million “very low-income” families in Florida are “severely cost-burdened” with more than 50 percent of their income going towards housing costs. And, according to research done by the University of Florida, nearly half of them, 45 percent, live in Miami-Dade and Monroe Counties.

Homeless advocates routinely point out the domino-effect of such high costs: If a family’s need to pay their rent or mortgage payment compete with other basic needs, such as food, child care or healthcare, they are at risk of homelessness.

Miami Homes For All, a non-profit committed to addressing the issue of housing affordability, launched an initiative to try and relieve some of the pressure on low-income households by partnering with investors, developers and public agencies to provide low-interest loans to incentivize the production of affordable housing.

Though housing affordability is a factor, people become homeless for a number of reasons, according to the Salvation Army, including drug or alcohol abuse, domestic violence and mental illness. But poverty, unemployment and not being able to afford a place to live can also force people onto the streets.

According to so-called point in time data, a random count that tracks how many homeless people are in shelters or on the streets, homelessness actually decreased since last year, however De Leon said this data doesn’t count people who are hiding out for their own safety or who are homeless by “other” definition, such as couch surfing or doubling up.

“Those numbers don’t reflect a much bigger story of how shelters are always full, how folks return to shelter, how women/children hide in plain sight, how The Homeless Helpline gets about 7,000 calls per month for help, how folks get evicted, how people are cost burdened or severely cost burdened, how in the City of Miami there is an unmet need of 32,000 affordable units,” De Leon wrote in an email.

Dennis Culhane, a professor of social policy at The University of Pennsylvania who specializes in homeless issues, said governments trying to put a dent in homelessness need to attack the problem from both ends: By increasing the number of housing vouchers and providing direct subsidies to renters, while also encouraging housing managers to set aside a number of units for low-income families by offering discount interest rates on developments as an incentive.

“So, they could increase both of those and increase the number of affordable units by a million. You know, that would have a big impact because it targets the people who are most negatively impacted,” Culhane said.

Cutting government out completely is also possible, Culhane said, but calls for a more creative approach. Large non-profits, like hospitals and universities, could intervene and provide subsidies to their employees in an effort to help them afford housing locally, he added.

In some markets, Culhane said, cities, companies and non-profits have already purchased a block of housing that is then used as low-income residences.

Being that homelessness and housing affordability are both complex issues, coming up with a solution is going to take a lot of creativity and partnerships, De Leon said.

“The thing is we need affordable housing,” De Leon said. “We need to preserve the housing we’ve got and we need to be creative.”

This story has been updated to reflect the most recent point-in-time data for the city of Miami.

Email: latinoreporterofficial@gmail.com

Twitter: @bella_paoletto1