Surveys on newsroom diversity conclude that the numbers are not changing

When Francisco Vara-Orta began his career in journalism more than a decade ago, he recalls being told by white and non-white colleagues alike to put his head down, do his work, and avoid addressing the lack of diversity in the newsrooms.

“I was told to stay away from race as a reporter and not bring it up in the newsroom,” Vara-Orta said. “People viewed those that brought up race as a problem instead of racism as the problem.”

Today, Vara-Orta is a data specialist and staff writer for Education Week where he is the only Latino in the news department. Though he is still one of the few minorities at his job, he believes there is more consciousness on why diversity in newsrooms is essential.

Though the numbers of journalists of colors have increased and several news organizations have begun taking steps to improve their transparency and the diversity of their staff and content, the small numbers still show the lack of progress and representation that exist in newsrooms today.

“We are placing ourselves into a corner of irrelevancy if we do not embrace talking about race,” Vara-Orta said. “How we cover it and how we handle it in our hiring in newsrooms.”

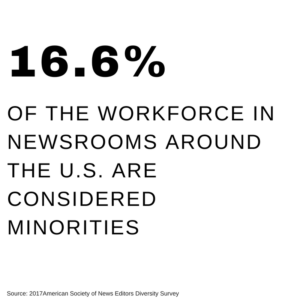

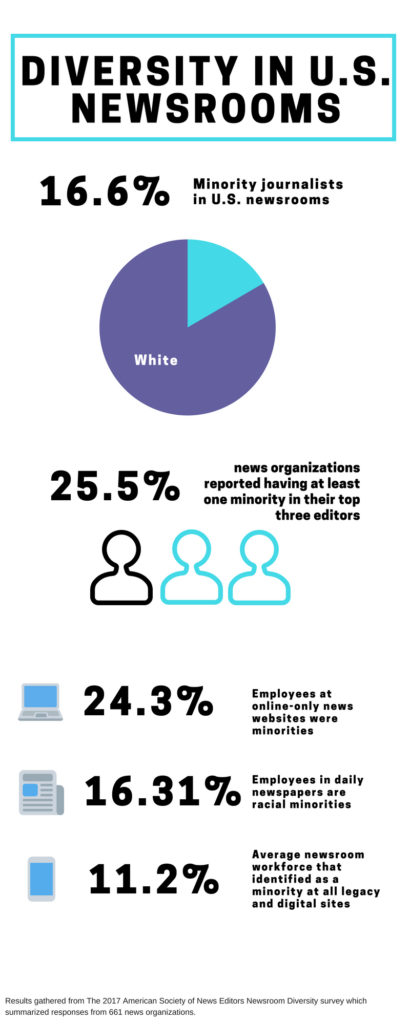

The 2017 American Society of News Editors Diversity Survey revealed that 16.6 percent of the workforce in newsrooms around the United States are considered minority journalists. This is about half a percent lower than last year’s number of 16.94 but higher than the percentages the ASNE has recorded for most of the past two decades. This survey only takes into consideration the newsrooms that did respond to the survey which were 661 news organizations.

Addressing diversity

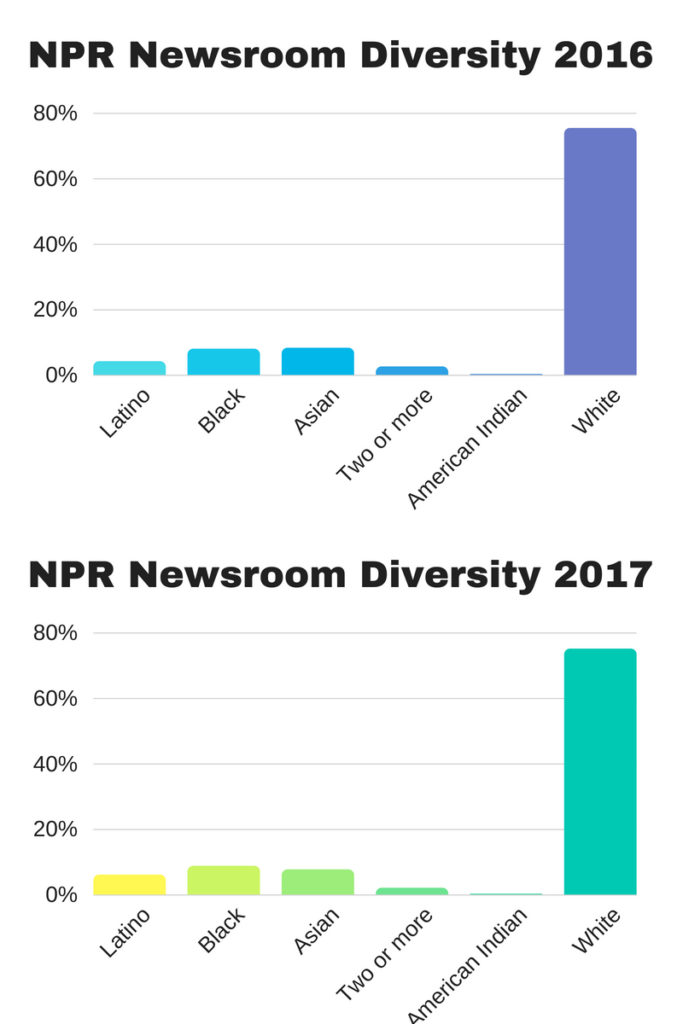

For many years, newsrooms did not reveal their diversity numbers. But that has started to change in recent years, as a growing number of newsrooms have begun releasing statements about their mission to recruit more diverse staff as well as numbers on how diverse they actually are. The diversity they take into consideration ranges from race, gender, religion and sexuality. Some of these results show that companies such as NPR remain almost unchanged.

The NPR Staff Diversity of 2017 revealed that it rose almost one percent in Latino and Black staff members, but dropped in its Asian and multiracial staff.

As a Latino reporter, Vara-Orta said it is his duty to ensure the Latinx community has a voice in his organization and in their content. Through his experiences, he has learned the complexity that comes with identifying as Latino since this group is not monolithic. As minority journalists progress in their careers, Vara-Orta believes, they try to find places that will be supportive of their identities.

Esmeralda Bermudez writes about the lives of Latinos for the Los Angeles Times. She recently wrote a story about a father whose son was taken from him by the government shortly after arriving in the United States. Bermudez, a daughter of immigrants, knows on a personal level what it is to be separated from her parents at an early age.

“I have felt child separation on my skin,” Bermudez said. “There is a connection that I am able to make that someone who basically has never gone through that would never even think about.”

Due to her experiences and knowledge of immigration and Latinos, Bermudez believes that what she will carry in her notebook after an interview with an immigrant will be deeper than what other reporters have. After the immigrant father was interviewed by many news organizations, Bermudez was able to get his phone number. The phone call Bermudez had with this father later that day made a difference in how this family’s story was told.

“His voice was heard on a whole different level versus what was told on ABC, NBC and other places,” Bermudez said.

Reporters like Bermudez or Vara-Orta want to shed light into the worlds of their communities and have been able to overcome obstacles when being the only people of color in their newsrooms.

“I do feel a responsibility to ensure that Latinos have a voice in the organization and in our content,” Vara-Orta said. “I feel that if I am not talking about them then I am not really of much use to my organization or the communities that I come from.”

Bermudez’s first job was covering city government at The Oregonian where she calls herself a “rarity” since she was one of the few Latinas in the newsroom. While she sat in city council meetings writing about the city budget, she saw the Latinos outside the building and the struggles that they were having.

“It was excruciatingly difficult that I was literally so close to them,” Bermudez said. “Though they were visible to me, I couldn’t reach them. I couldn’t tell their stories.”

Once Bermudez began to write about the Latino community for The Oregonian, she had to explain her stories so her white editor and non-Latino readers could understand everything.

Over the past 10 years, Bermudez has written on a variety of topics ranging from the Mexicanization of Salvadorans to the obsessions Latinos have with San Marcos blankets.

“I will be so happy if every hair on my head turns white and I am still doing this job always writing about Latinos,” Bermudez said. “It’s the most important thing that I could possibly do as a journalist.”

When the 1968 Kerner Commission was established by President Lyndon B. Johnson to investigate the causes of race riots in the United States, one of its solutions was to hire and train more black journalists since these riots were happening in areas with high concentrations of black people.

Meredith Clark, assistant professor of Media Studies in the University of Virginia, who is directing the 2018 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey, says a crisis related to that of 1968 is occurring today.

“The crisis of the time now is more diverse,” Clark said. “But we are still taking on issues of police brutality and this immigration crisis which the president has manufactured.”

Clark says that minority journalists are necessary in all newsrooms to accurately report the communities of color their organization serves.

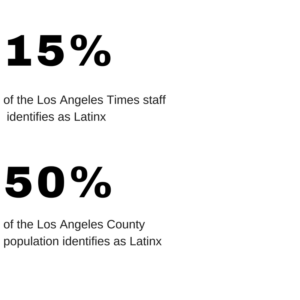

This is not always the case for many communities, such as in Los Angeles where Bermudez works. While Los Angeles County is almost 50 percent Latinx, less than 15 percent of staff members at the L.A. Times identified Latinx. This does not reflect the region they serve.

Bermudez said the percentage of Latinos at the LA Times is not acceptable. The percentage includes a variety of Latinos from designers, copy editors, photographers, reporters, and others on staff. Her dream is for the L.A. Times to be present in the communities of color especially the Latino community so they feel invested in the publication and know that they too are visible and that their stories matter.

“I want Latinos to see themselves and their lives reflected in the paper,” Bermudez said. “I want them to pick up the paper and say ‘I know this guy from high school or I experienced this when I first came to this country.’”

Vara-Orta said one of the reasons people of color do not follow major news organizations in their area or those that reach a national audience is because they are not having stories or content that cater to their specific demographic.

“They [people of color] may not see themselves in The New York Times, The Washington Post, or CNN so they are going to look elsewhere,” Vara-Orta said. “If media institutions want to stay relevant and stay afloat economically, they have to think about the future and who they are serving and who they have already lost.”

As Clarks conducts the 2018 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey, she said that when newsrooms provide their demographic and diversity data, it shows transparency. In order for journalism to keep up with the changing populations and views of America, Clark said companies need to have people who can connect to a variety of communities.

Bermudez said that when Latinos in Los Angeles think of the L.A. Times they think of her face. Though she is a representation of their community, she wants more Latino and other minority reporters out in the neighborhoods reporting about their communities and showing up to their meetings or parks and talking to the paleteros, the taco truck vendors, the moms walking their kids to school, the doctors, the actors, among others.

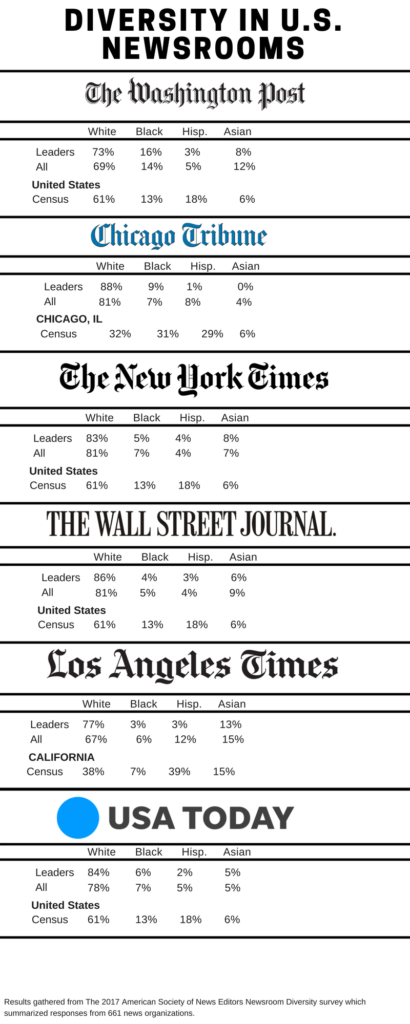

When the Columbia Journalism Review conducted a study of the breakdown of the political press corps of 15 major news outlets during the 2016 election, only USA Today, The New York Times, NPR, and The Washington Post provided the requested data. Though this was just a look at the political reporting teams, the data showed that over 50 percent of the staff identified as White.

When newsrooms do not disclose their demographic data to surveys such as the one done by the CJR or ASNE, it is hard to have an estimate on the accuracy of racial diversity in newsrooms.

“We don’t know how bad or good it is,” Vara-Orta said. “It is important to keep calling out our own industry because here we are always wrecking hollywood, the tech industry and political structure for not having people of color being representative of their communities but the media is just as bad at it.”

Increasing the numbers

Newsrooms across the country have incorporated different sorts of programs, fellowships, policies or ways to recruit and hire more minorities. For example, ProPublica has what is called the “Rooney Rule.” This rule consists of the company interviewing at least one person of color for every job they have posted. The New York Times has established their Student Journalism Institute to provide training for diverse college students who want to become journalists. Associations such as the National Association of Hispanic Journalists, National Association of Black Journalists, and the Asian American Journalists Association are also some of the ways recruiters and companies seek diverse representation in their workforce.

Institutes such as the Poynter Institute offer programs that support journalists of color. Some of the programs they conduct are The Power of Diverse Voices: The Poynter Minority Writers Workshop and the Poynter-NABJ Leadership Academy for Diversity in Digital Media. The Maynard Institute strives to help the news media portray communities of color accurately. Some of the ways they achieve this are by having trainings for managers, recruiters and journalists of color as well as by creating content that display why voices of color are needed in the field.

Vara-Orta said that one of the biggest challenges reporters of color face is not having access to the schools or programs where these companies recruit. Another challenge is seeing more diversity in marketing or public relations industries and seeing how more pay these other jobs offer as well as paths towards promotion.

“There is a bias I have detected that the only reason we are there is because of diversity programs,” Vara-Orta said. “There is a lot of push of having internships and fellowships but what about promotion to management, what about promotion to editing where you are making the decisions?”

The 2017 ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey showed that about a quarter of news organizations reported having at least one minority among their top three editors. Having newsroom leaders not connected to their diverse communities will likely not lead to more inclusive newsrooms according to Clark.

The incorporation of journalists of color in a newsroom does show how newsrooms are taking a step towards inclusivity. But not every person of color in a newsroom wants to write just about race like Bermudez does.

“Race is not the beat,” Clark said. “The beat is race and how it impacts economics, education, business, real estate, and everything else that outlets report on. The beat should be inclusive because race matters.”

When Bermudez graduated from the University of Southern California, she was accepted to the Metpro Training Program which aims to help launch the careers of diverse journalists and place them in top newsrooms such as the Chicago Tribune and the LA Times. Though programs like these have proven to be effective for some, Bermudez believes that top reporters of diverse backgrounds are not being nurtured or guided as they should be at the beginning of their careers.

“You end up having this cheap labor of people of color,” Bermudez said. “A lot of them have this tremendous talent of being shaped and molded into key players in our newsroom, but as of now it hasn’t happened.”

This year’s ASNE Newsroom Diversity Survey will allow minority journalists to answer questions such as how it is to work at their companies as a minority and reasoning as to why they have left past jobs. This will give the ASNE more of a perspective that can give meaning and context to the numbers the survey gets every year. Thinking ahead to the future of minority journalists in newsrooms, Clark said that new ways of addressing this issue need to be developed in order to see results.

“It is time for us to develop metrics that help individual organizations measure their commitment to diversity in ways that are meaningful to that organization,” Clark said. “It is time for us to think about how do we create a common goal of achieving parity with the communities that these outlets serve, but more in a way that speaks to their specific demands and challenges.”

A simple solution to the low numbers of journalists of color in the newsroom could be to hire more people of color and to train staff to become culturally competent in communities unlike themselves. Though easy to say, the ASNE survey results show that it the past two decades of results are a work in progress.

Bermudez believes that an investment in mentoring and being able to identify different talent individually in journalists of color can allow them to contribute in newsrooms in ways they feel passionate about.

“It is going to take the entire industry to address this,” Vara-Orta said.

Email: latinoreporterofficial@gmail.com

Twitter: @diego_pineda19