Latinos struggle with mental health, seeking care as deadly coronavirus rips through their communities

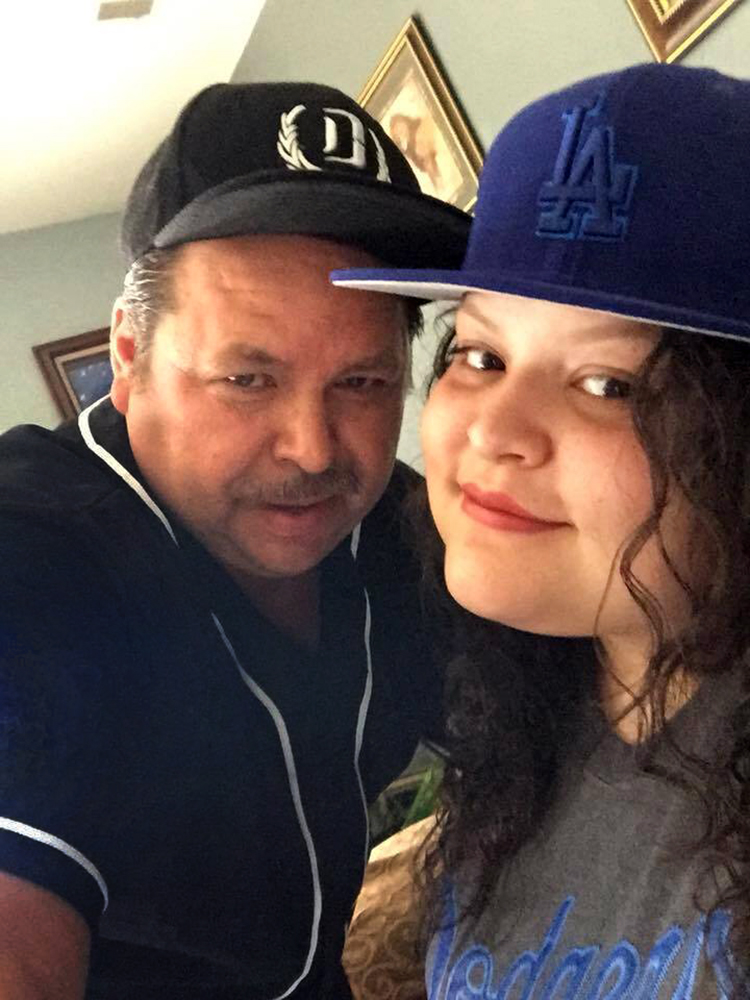

CANOGA PARK, Calif. — Jeanine Guerrero and her family of 10 got together on Memorial Day weekend for carne asada, Jenga and Nintendo Switch. For the first time since the lockdown began in mid-March, they felt the world was getting back to normal.

California had eased its stay-at-home order, and because the Guerrero family didn’t know anyone who had contracted the deadly coronavirus, they thought it would be safe to see each other.

Eight days later, Guerrero’s uncle fell ill and was taken to the hospital. Guerrero began to feel tired. She spiked a fever.

From the hospital, her uncle suggested other members of the family should take a COVID-19 test.

Guerrero, 29, did. When the results came back, her stomach dropped: Positive.

Latino communities around the U.S. have been pummeled for months by the still-spreading coronavirus. They’ve fallen ill, lost jobs, buried people they love. Bills continue to roll in. The demands of daily life remain. The mental health toll, experts have said, is extreme. But for many Latinos, it’s not always clear where they can turn for help. Latinos face barriers to mental health care, according to the National Alliance of Mental Illness (NAMI), both in access and in quality of treatment. These barriers include, but are not limited to, language barriers, health insurance access, lack of cultural expertise and a cultural stigma.

The bad news kept coming for the Guerrero family.

When her brother’s employer found out her results, Guerrero said, they told him not to come back. Her mother and father had also stopped working. Guerrero said her father lost his job after his company went bankrupt. Her mother hasn’t worked in three years due to an injury.

“And that pressure just built up on me,” she said. “Like, ‘Oh my god, you need to feel better so you can get back to work and keep providing. Like, you’re the sole breadwinner of the household — you need to snap out of it.'”

Guerrero, a Mexican American living in Los Angeles, knew she couldn’t help her family alone. She needed help with her mental health.

A study published in July by the UCLA Latino Policy and Politics Initiative found that the Black and Latino populations in Los Angeles and New York City are twice more likely to die from coronavirus compared to the white population.

One third of Hispanic or Latino adults with mental illness receive treatment each year compared to the U.S. average of 43 percent for the overall population, according to NAMI.

The effects of coronavirus have created more mental health concerns, such as the fear of testing positive, personal worries, domestic abuse, loss of income and family loss.

Guerrero is part of the small segment of the Latino community who have sought mental health services.

Falling sick created a lot of stress, but the thought of who was going to provide assistance for her family motivated her to get better.

“There was that fear of what’s going to happen if I don’t make it out, who’s going to keep supporting the family—nobody else is working,” Guerrero said. “I need to get better so that I can keep this household running so that we can keep the bills getting paid.”

Guerrero said that after her test results came back positive, she spoke to her employer about her family concerns.

“At that moment you feel like, ‘How am I going to pay for our bills next month? How am I going to pay for the rent? How am I going to pay for this and that?’ All those fears on top of feeling really ill just got to me,” Guerrero said.

Guerrero said she has experienced depression and anxiety. She added that because her coronavirus physical symptoms were worse than her mental concerns, she was too exhausted to think about her other fears. Her exhaustion made her sleep more. She wanted to rest more to get more strength to feel physically better.

Despite self-quarantining in the guest section of her home, Guerrero wasn’t alone in managing her health. Her family brought her vitamins. One of her closest friends routinely checked in on her. Even social media helped her connect.

Guerrero’s health care provider also provided support by reaching out to her with resources and connected her with a physician, who asked her if she needed a place to stay outside of her home to quarantine.

Guerrero said she and her family did not believe the coronavirus was a hoax. But she didn’t think it would impact her family because she didn’t know anyone who had it.

She encourages people to limit their social gatherings to only their household. At the moment, Guerrero has physically recovered from her coronavirus symptoms and is working from home.

“Yes, we all miss our family members,” she said. “Yes, we miss our friends. But are we willing to pay that price? Don’t we have hand sanitizer at home? Why aren’t we washing our hands as frequently when we’ve had this message since March? Why are people so against wearing their masks when a mask can literally save you from getting something that the person across from you has?”

Ana Gonzalez, a family educator for NAMI Urban Los Angeles, said it’s hard for Latino families to talk about mental health.

“The first thing we have to realize about our community is the stigma – the taboo,” she said. “We cannot talk about it. And that is in every family.”Gonzalez said there’s an expectation to dismiss concerns about mental health because there isn’t an easy to way to bring up the subject for Latinos.

“‘Oh no, no te preocupes (don’t worry),” she said is a response that a family member might give if you bring up mental health concerns. “You’re going to go through to this. You don’t need that. Nobody believes in that psychiatric. [Nobody believes] in therapists. You can handle it.”

Gonzalez said her young son has schizophrenia paranoia and that he doesn’t understand why coronavirus is out there. She said he would wonder why people needed masks. His therapist would explain the reasons to him, she said, but then he would forget, which led to more repetitive conversations.

He would get frustrated or anxious when they couldn’t go outside, she said.

“Why? Why? Explain to me,” Gonzalez’s son would ask her.

He would also tell her that coronavirus isn’t real.

“It’s nothing. It’s not contagious. Nothing is going to happen,” she recalls what he would say.

For Latinos living alone, coronavirus impacts their mental health differently.

Mykel Saucedo was at work and masked when he began feeling ill. At first, he had thought he was just dehydrated, so he brushed the feeling off. As the day went by, he felt his whole body ache and had to sit down.

Saucedo napped in his car when he finished work because he felt too drained to drive home. After waking up, he knew something was wrong because he had never felt the way he was feeling. When he got home, he immediately isolated himself.

After sipping some tea and sleeping it off, he woke up the next day with a fever. As he walked to the restroom, he felt as though he was hunched over and fragile, as if he had done an intensive workout. He felt chills and had a fever and a headache. That night, he vomited.

He wasn’t living with his family, so he felt alone and scared. He drove to the emergency room.

After doctors evaluated him, Saucedo took a coronavirus test. He had to wait for at least three days for his results, so he continued to isolate himself. Soon he learned he tested positive.

He called his mother about feeling sick. His mother tried to reassure him that he would be fine. However, he said that looking back, he thinks she knew but did not want to scare him.

“Besides being physically [drained], I think the whole first week that really took a toll on me was not being able to be with my mom, especially because I actually am very family-oriented,” said Saucedo, a 24-year-old Mexican American currently residing in Los Angeles.

At first, he didn’t want to talk about the coronavirus diagnosis. While he was not looking for sympathy, he did see many people messaging him and genuinely caring for his well-being.

However, Saucedo said he was not too concerned about his physical health.

“Right off the bat, for me, the main stress was the people around me,” he said.

He communicates with his roommates through a group chat. He said the communication helps everyone know who is in the kitchen or in certain areas of the household, as well as if they can safely give him something he needs.

If he goes out of his room, he would sanitize everything he touches.

To help cope with his mental health, Saucedo has been going out to his backyard, binge-watching movies and reading, analyzing and studying several skincare products. His primary doctor, who is three hours away, would call him every day to check if he is OK.

At the moment, Saucedo is feeling better from coronavirus.

Guerrero said there are free resources and counseling groups for Latino and Hispanic communities that people can attend. However, she knows that there are barriers for people to want to seek services. She said that the first thing Latino communities should do is to talk about it.

“We need to talk to our peers, our family members, our friends and realize that we’re not the only one having these thoughts, having these emotions, having these feelings that we’re going through,” she said. “So, we all need to step out of our own shoes and literally look at what our neighbor is going through.”And when we do, that is when we realize we’re not alone,” Guerrero said.

Resources for mental health can be found on the NAMI website.

Eduardo Garcia is a junior at California State University, Northridge, where he specializes in broadcast and Spanish-language journalism. He is a video editor for CSUN’s El Nuevo Sol, a bilingual multimedia publication. Reach him at eduardogarciamedia [at] gmail [dot] com and on Twitter @eduardogarciatv.