Once ignored, Mexican-Americans commemorate their contributions in Nebraska

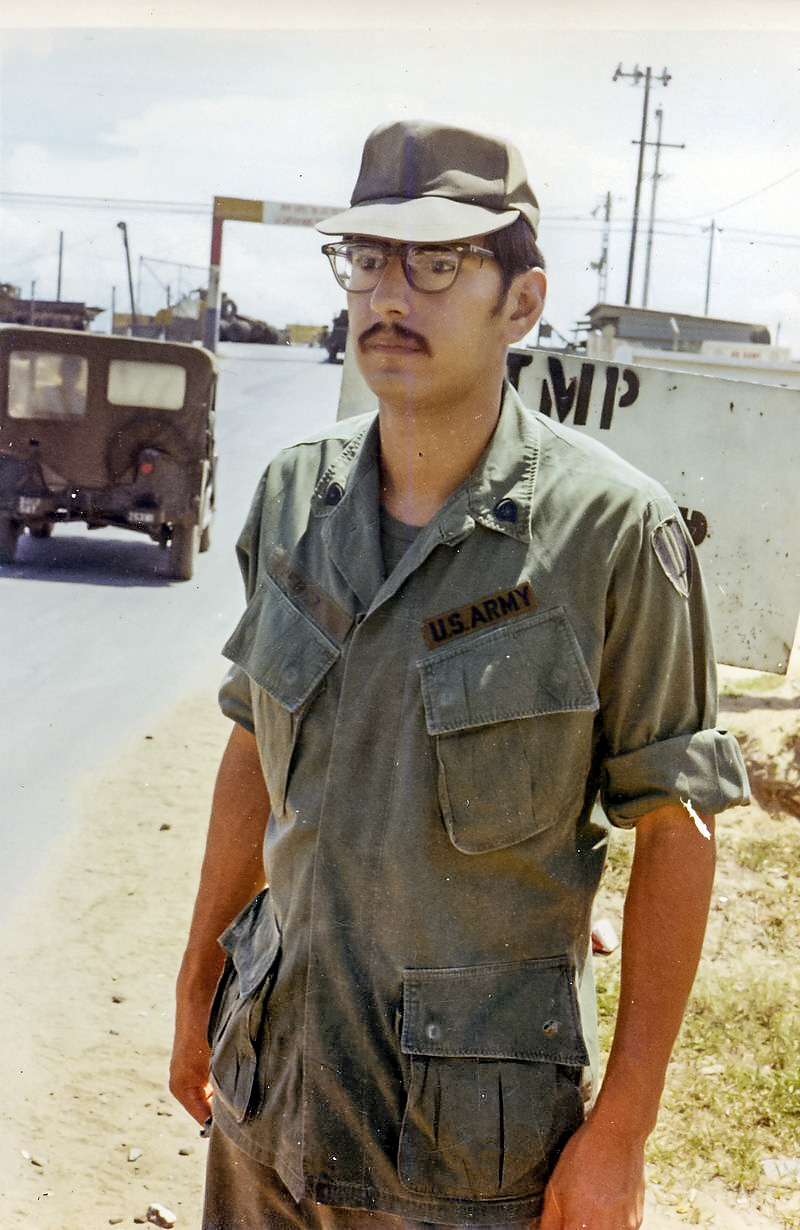

LINCOLN, Neb. — Marty Ramirez is no longer reluctant to talk about his service in Vietnam.

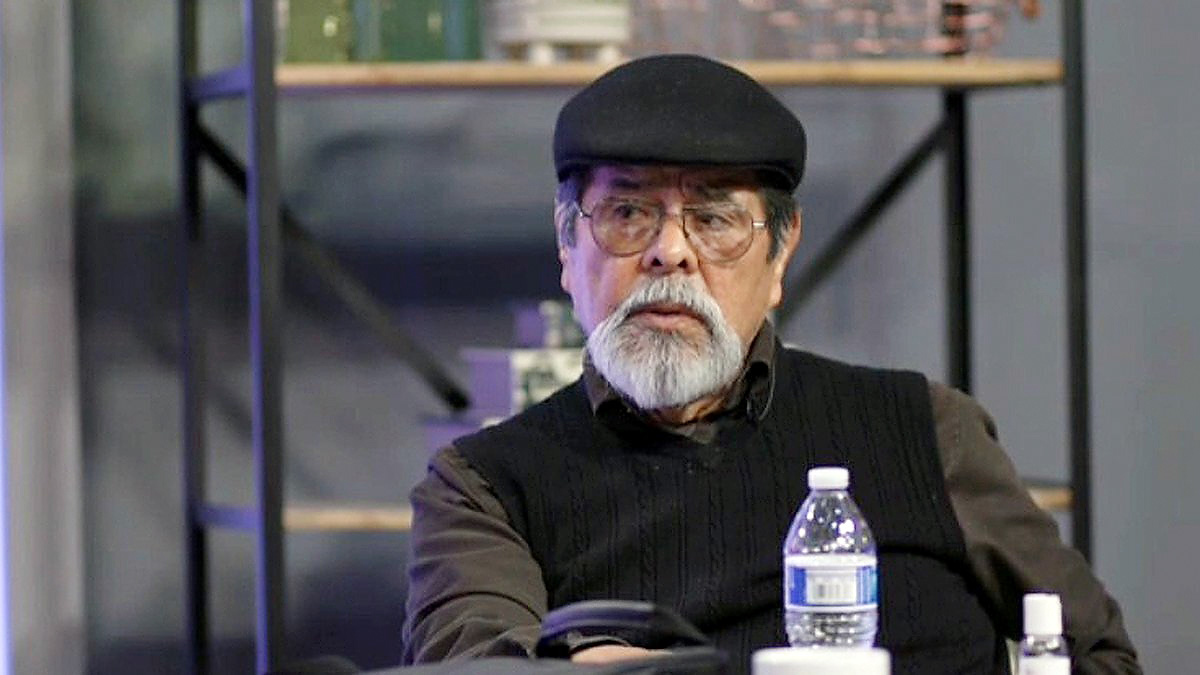

The 77-year-old now wears a gray shirt that reads, ‘Vietnam,’ and a black, Purple Heart cap.

The historical discrimination against Mexicans didn’t allow Ramirez to open up about his time in Vietnam upon his return home in 1969.

“When we were in the uniform, we almost felt like when do things change? Will they ever change? Is it always going to be the color of your skin?,” Ramirez said.

Two months ago marked 60 years since Ramirez and his childhood friends went their separate ways.

But it was just 5 years ago that a class reunion revealed that although graduation took them separate routes, they all ended up serving in the Vietnam war at different times.

“We started catching up on our life experience, and came to find out that all of us had served time in Vietnam at different places and at different times,” Ramirez said.

While Latinos have been a part of Nebraska’s history for over a century, their contributions have rarely been recognized.

As decades passed and Mexican American veterans lacked the same acceptance as their white counterparts, Ramirez and other veterans took it upon themselves to recognize their service in the form of a monument in Scottsbluff, Neb., their small, predominantly white hometown.

“I think what it (the project) does is it instills pride in the people that are still in Scottsbluff and the youth see that their life doesn’t end there in Scottsbluff,” said Greg Rodriguez, a Vietnam veteran who served from 1965 through 1967.

Taking a risk

They called themselves the Barrio Boys. They first experienced racism in grade school— something that greatly bothered them.

The Barrio Boys included Ramirez, Jose Perez, Ben Salazar and Greg Rodriguez, and many others from the barrio who lived similar childhoods.

Growing up in the barrio, they understood their lives were vastly different from those of their white classmates. On the southeast part of town — the barrio — one could find unpaved roads, no streetlights and rundown homes.

They also had limited opportunities for jobs. Many of them ended up working in the sugar beet fields nearby.

“Many of Latino kids back then, we weren’t encouraged to go to school beyond high school,” said Ben Salazar, who served in Vietnam from 1966 to 1968.

Despite that, 12 out of the 22 Mexican students in their graduating class obtained college degrees at some point in their lives.

Some attended after their time serving, some answered the call to service after receiving a college education.

They came from patriotic homes, where it was common to see a wall of photos dedicated to the servicemen in their families.

That’s why they all answered the call, they said.

“We were all brought up thinking we were going to go to the service,” said Rodriguez. “You know the John Wayne mentality of let’s go to war, we’re going to fight.”

It wasn’t so much that they wanted to fight, they simply knew it’s what they had to do. Unlike other men, they couldn’t even think about dodging the draft.

For them, and like many other Mexican American men, dodging the war was something that would’ve reflected bad on their family.

“There were individuals who were escaping the draft by going to Canada, but I was reluctant to go,” said Jose Perez, a veteran who served from 1969 through 1971 in Vietnam and in the National Guard for 24 years. “I did not want to disappoint my parents and be unpatriotic.”

A long time coming

For these veterans, this project was just a blimp on the lives of activism they each went on to lead upon returning from the war. But their activism truly began in their hometown of Scottsbluff.

They would later find out that 60% of the Mexican men in the Scottsbluff Class of 1963 were drafted.

For Salazar, the first sacrifice came in the 21 days he spent on the Pacific Ocean going to Vietnam.

He recalls being scared and sad about his circumstances.

“I turned 21 on Halloween on the deck of this old freighter tearing up. Laying on my back, looking at the stars thinking, ‘Why me?’” said Salazar.

That same question, ‘Why me?’ was what they had asked themselves growing up in a segregated Scottsbluff, facing discrimination.

It was now nearly 60 years since they had left Scottsbluff, Ramirez said things had slightly improved and their recognition was due.

“The monument tells a story that nobody can argue. Not even the most racist people can argue with our history,” he said.

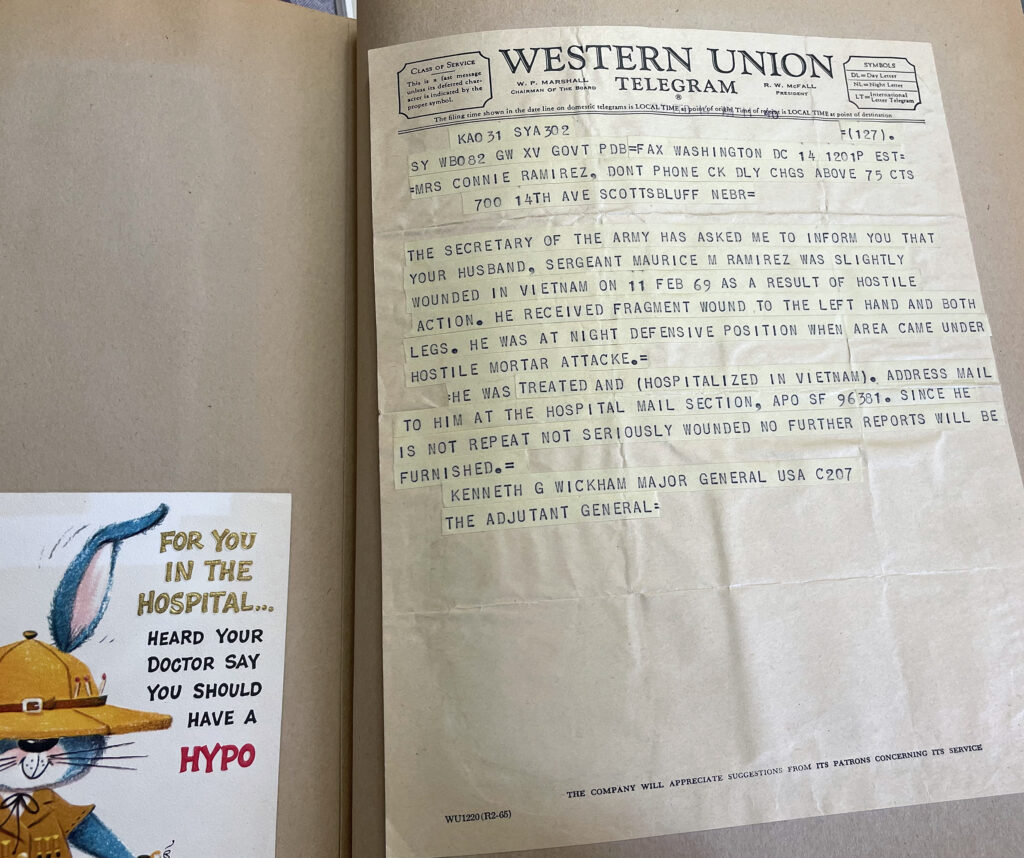

The Western Union Telegram Ramirez’s wife received after he was wounded in Vietnam. Ramirez still has shrapnel scars and experiences occasional numbness in his leg. Photo by Evelyn Mejia.

Activism wasn’t something any of them planned, but their barrio days and the time they spent in Vietnam prompted it. They always wanted better for themselves and once they achieved it upon leaving Scottsbluff, they wanted better for their community.

Careers in human affairs, psychology and journalism provided valuable knowledge that aided their activism.

Their work impacted the livelihood of Latinos in Nebraska.

Salazar, was a cofounder and first President of the Mexican-American Student Organization (M.A.S.A.) at the University of Nebraska at Lincoln, Nebraska’s largest public university.

Decades later, through their meaningful impact, they no longer felt as second class citizens or veterans.

When Perez had the idea to commemorate their impact and service, it was easy for the Barrio Boys to band back together. They had always been proud of their heritage, their roots. The pride never lacked, but they wanted to commemorate their legacy.

The four marble monuments, each with names of Mexican-American veterans, and a bench, did just that.

Sitting in front of the Guadalupe Center — what they describe as a historical marker for the Scottsbluff Mexican-American community — their contributions can’t be ignored, Laura Muñoz, a history and ethnic studies professor at UNL says.

“I think the biggest impact is the presence the monument has created,” Muñoz said. “I think that it’s changed the way that perhaps the community in Scottsbluff sees the participation of these Mexican American veterans.”

Forgotten due to the unpopularity of the war and their ethnic background, these veterans answered the call and made the biggest sacrifice possible for this country.

That’s why leaving a legacy was essential. By doing so, young Latinos would see themselves represented in their state’s history –something they never experienced.

This commemoration, Ramirez said, lets the community know that while they’re Mexicans who happen to be American, they are not second class citizens or veterans.

Evelyn Mejia is a senior at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln majoring in journalism with a minor in Spanish. She is currently a fellow at The Flatwater Free Press and aspires to become an investigative reporter. Reach her at evelynmejiasal [at] gmail [dot] com or on Twitter at @evelynmejiaaa.