Journalists absorb trauma from the events they cover. Here’s how some cope

Hours after a man walked into the Pulse nightclub in Orlando and opened fire, killing 49 people and wounding 58 more, Arelis Hernández boarded a plane to the place she once considered her home.

Hernández, a journalist with The Washington Post, was on her way to the Florida city to report on the aftermath of the attack. As she sat there on the plane, Hernández silently sent up a prayer that none of the victims were her own family or friends.

In her 3 years at The Post, Hernández has been sent to the scenes of crimes, flooded cities and chaotic protests. But for the most difficult stories she’s covered, she said, she has had to learn to shut down her emotions.

For many journalists thrust into the emotional turmoil of terrorist attacks, war zones, natural disasters — or everyday crime and destruction — one of the most challenging parts of the job can be dealing with the trauma and devastation of others. How those interactions affect them, and their own mental health, is often ignored or downplayed by a group of professionals whose guiding principles include never making the story about you.

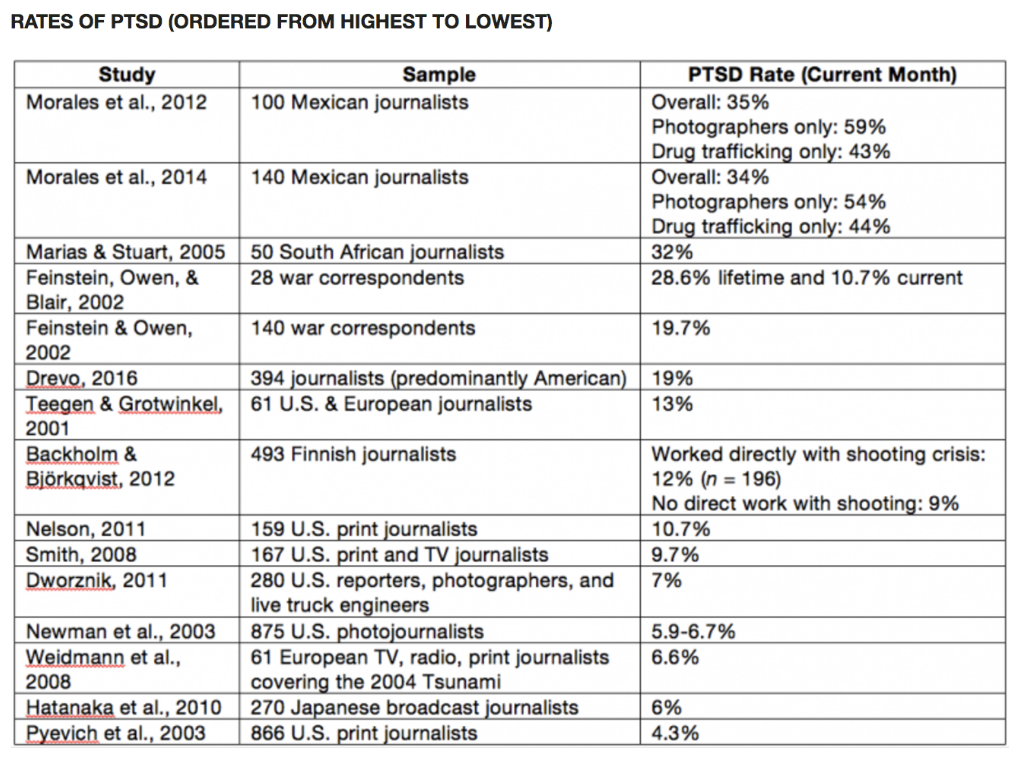

About 19 percent of American journalists suffer from Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), according to a 2016 study from the Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma.

But many more, between 80 and 100 percent of journalists, have been exposed to work-related traumatic events, according to the Dart Center study.

“We see a lot of ugly, horrible, bad things that happen,” Hernández said.

Candy Rodriguez, a multimedia journalist in southwest Louisiana, just returned from covering Hurricane Harvey’s impact on the region. During times of tragedy, she said, even as they focus on informing the public, journalists are also affected by what happened to the people around them.

“It’s hard not to feel emotion when you are talking to [people],” Rodriguez said. “I would be lying to you if I told you that I never got teary eyed.”

During a session at the Excellence in Journalism conference in Anaheim, CNN correspondent Nick Valencia said he worries about the mental health of his fellow journalists.

“I struggle with mental health, but I talk to people. I talk to therapists. I talk to my wife. I cry,” said Valencia, who recently returned from covering Hurricane Harvey. “I think we’re one good cry from being alright.”

When she was 14, Zalome Briceño moved from Peru to North Palm Beach, Fla. Straddling two cultures and speaking two languages pushed her to become a bilingual multimedia journalist.

Briceño began working on her journalism career in high school. She attended a magnet school which focused on television, radio and film production. After graduating, Briceño enrolled at the University of Florida, where she is pursuing a degree in communications and political science.

Though she enjoys covering hard news stories, Briceño has an affinity for investigative reporting.

“I always say to myself never close doors,” Briceño said.

She hopes to work in both Spanish and English media.