Journalists of color urge newsrooms to call out racism

Julio Ricardo Varela resents being accused of bias when he is reporting on the Latino community. He is just telling it like it is.

Take the mass shooting at an El Paso Walmart, where a gunman who expressed anti-Latino views killed 22 people. Varela, part of Futuro Media’s team and co-host of “In the Thick,” a podcast that focuses on race, identity and politics, says it should be described as an act of domestic terrorism fueled by racism.

There are no two sides to that story, he says. “We have to be real, as journalists.”

But in newsrooms struggling to decide how to describe overtly racist language and acts, the lines are rarely clear.

Journalists of color, in particular, are often accused of bias when they push to label bigoted speech as racism, especially when those words are coming from the president.

Should, for example, this tweet — referring to four congresswomen of color — be called racist?

“Why don’t they go back and help fix the totally broken and crime infested places from which they came?”

How about when Trump referred to African nations as “shithole countries”? Or when he said there were “very fine people on both sides” during protests between white nationalists and those opposing them in Charlottesville?

An increasing number of journalists of color say media outlets should not be afraid to label certain language and policies as racist.

“I have colleagues in the media who are discussing whether or not to call what the president said racist. I wake up thinking about chants now that say ‘send her back.’ That’s me,” tweeted Maria Hinojosa, the anchor of Latino USA and founder of Futuro Media Group. “That’s a congresswoman. This is racist. To not say so is to have your head in the sand.”

Mainstream outlets, however, often won’t go that far, wrote Paul Farhi in the Washington Post, noting that many stick to “phrases best described as ‘racist-adjacent,’ ” such as “racially loaded,” “racially tinged” and “racially charged.”

“Racism in 2019, doesn’t look like someone necessarily spitting out racial epithets. It’s a lot of times in these coded political messages,” said Rachel Hatzipanagos, multiplatform editor at The Washington Post. “It’s our job as journalists to unravel and reveal the meaning behind what someone is saying.”

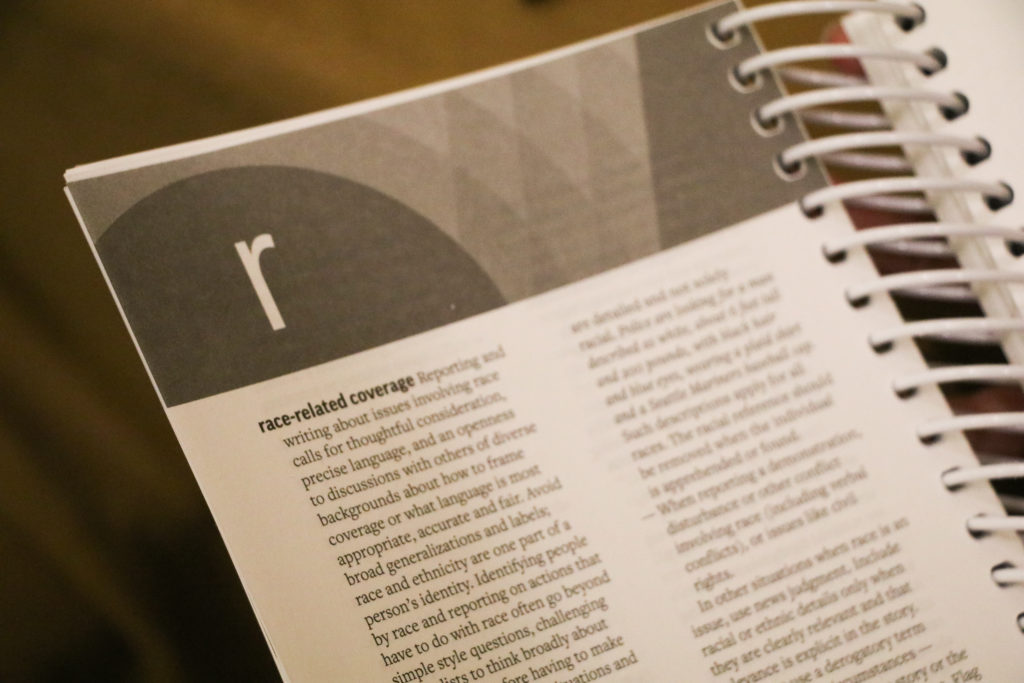

The Associated Press took a step toward clearer language when it updated its stylebook on reporting about race.

The stylebook now urges journalists to describe what makes something racist by being specific and avoiding the use of vague terms such as “racially charged” when the use of “racist” or “racism” apply. It also encourages conversations with “colleagues and others from diverse backgrounds” when deciding to term something as racist.

“In newsrooms that are prominently run by white men, newsroom leaders should always seek to listen to the input from journalists of color in the room,” Hatzipanagos said. “And, as Latino journalists, we should really make a point to stand in solidarity with other journalists of color, because it’s only in working together that we’re going to impact change.”

Many journalists of color still face the possibility of being branded as biased because of the color of their skin, their background or connection to the subject. For some, it is something that also takes a toll on them.

The New York Times Magazine reporter Nikole Hannah-Jones said in a tweet that black and brown journalists “are having to deal with the psychic impacts of (Trump’s) racism.”

Errin Haines Whack, who reports on race and ethnicity for the Associated Press, says she constantly faces backlash and is even labeled as racist.

Whack does not believe covering racism takes a toll on journalists of color, but is instead “validating and affirming … because it is a form of truth telling and accuracy in journalism.”

Whack also highlights what many people echo in social media: the journalistic industry is not comfortable with talking about and reporting on racism.

“I know that for us to be providing that kind of guidance means a lot in the industry,” Whack said about the stylebook’s update. “It gives other outlets permission to have this conversation and to make their own decisions about what they’re going to do in their newsroom … It is an issue that my editors and I have conversations about, sometimes we land on the label and sometimes we don’t.”

The August 3 El Paso shooting, where eight out of 22 people killed during the shooting were Mexican nationals and most of the other victims were Latino, encouraged many Latino journalists to speak out.

“We’re living in a culture that has allowed for this type of language to criminalize and demonize,” Varela said. “We’ve allowed this to happen as journalists.”

He warns that there will always be people who say journalists of color should not report on racist incidents within their community because of their bias, but there will also be people who value it.

Varela also does not feel that reporting on race takes a toll on him because of the people who reach out to thank him for his coverage.

“That drives you,” Varela explained. “It drives me.”

Keith Woods, NPR’s senior vice president of newsroom training and diversity, said in a recent Code Switch episode that he believes that journalists’ job is only to report and not to cast judgement on what is racist.

“I think that the urge that we have now, which I believe is motivated by our desire to hit back,” Woods told Code Switch, “to label things and people racist, in the end, is a slope that we will slide down so fast and damage the instrument of journalism, which is one of the few instruments we have to fight exactly this kind of thing.”

Marc Duvoisin, editor at the San Antonio Express-News, explains instead of simply labeling something as racist, journalists should instead describe it “in terms of its effect or its content.” Their audience is then able to fully understand what makes a phrase, action or policy racist.

“I like to avoid general labels and try to be as descriptive as possible, and specific,” Duvoisin said. “The term racist has become very broad.”

Duvoisin said when someone becomes a journalist, they are committing to a “professional discipline of detachment” in which their own beliefs should not influence the way they report about a topic or subject.

But Woods says that journalists are human and that they will almost never be able to fully detach themselves from their reporting.

“Why should I trust that we’re all on the same page with our labels now? Weren’t last week’s tweets racist? Or last year’s? Weren’t some misogynistic? Vulgar? Homophobic? Sexist?” Woods wrote in an opinion piece for NPR. “The language of my judgment is generous, and they are my opinion, and they belong in the space reserved for opinions.”

Woods added that journalists should add context instead of assigning labels, leaving “the moral labeling to the people affected; to the opinion writers, the editorial writers, the preachers and philosophers; and to the public we serve.”

As an editor, Duvoisin believes that no journalist should be excluded from reporting a story to which they have a connection to because he expects them to be impartial.

“In some ways, you can be more effective in writing about something that you’re detached from, that you have no personal experience of,” Duvoisin said. “In some ways, it’s very valuable to know the terrain.”

The responsibility of calling out racism should not be carried solely by journalists of color, Whack added. White journalists should also be willing to consider using the term.

“If we’re reporting the truth, then that’s not biased. It’s simply a statement of facts,” said Hatzipanagos. “The more that some organizations get into writing things as euphemisms, the more trouble we get ourselves into, because we’re kind of muddling the truth.”

“It’s a long journey, things are not going to change overnight,” Varela said. “There’s people that have done the work before us, there’ll be people that’ll do the work after us.”

Valeria Olivares is a 2019 NAHJ Student Project participant. She is a junior at the University of Texas at El Paso and is majoring in multimedia journalism. She is the editor-in-chief of the Prospector, UTEP’s independently-run student newspaper. Reach her at valeriaolivares@gmail.com and on Twitter at @valeriaoliesc.