The border shaped his work: Lalo Alcaraz reflects on life, Latinidad and his biting humor

Growing up as a self-described “poor, brown kid” in San Diego, Lalo Alcaraz heard the insults — heard that being Mexican was “the lowest thing possible.”

Then as a teenager, he took a trip to Mexico City, where he discovered that being Mexican, or Mexican American, is “cool.”

That trip, and those insults he heard growing up, molded him into the man, and political satirist, he is today.

Now, as the creator of the daily comic strip “La Cucaracha” — as well as a producer and writer of the animated sitcom “Bordertown,” and part of the team working on Pixar’s “Coco” — Alcaraz portrays the indignities, absurdities and challenges of Latino life in the United States, often with biting humor.

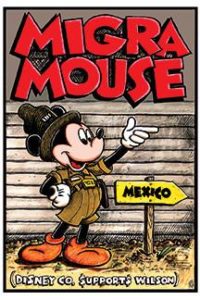

Back in 1994, he drew a cartoon featuring “Migra Mouse,” a smiling Mickey Mouse dressed as an Immigration and Naturalization Service officer. Alcaraz drew the cartoon in response to Disney’s support of then-California Gov. Pete Wilson, a leading force behind Proposition 187, which denied public services to undocumented immigrants.

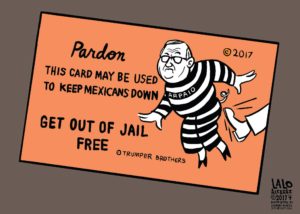

More recently, after President Trump pardoned Joe Arpaio, the Arizona sheriff known for his tough anti-immigration policies, Alcaraz drew a Monopoly-like card that reads: “Pardon. This card may be used to keep Mexicans down. Get out of jail free.”

But before “La Cucaracha” and “Coco,” Alcaraz lived in between two countries that shaped his identity and his work.

Alcaraz was born in 1964 in San Diego to immigrant parents from the Mexican states of Sinaloa and Zacatecas.

“We crossed the border every two weeks to buy groceries or whenever we needed to go,” he said about his experience living on the border, “and my mom would take me to see the lucha libre matinee.”

His understanding of Chicano identity came after years of being treated as any other Mexican immigrant — poorly and with a lack of respect — even though he was born in the U.S.

“I grew up bitter and pissed off, I’m still obviously bitter and pissed off,” he said, “I was that way for a long time.”

That anger and a sense of restlessness led him to run with gangs, though he says he was never a hardcore gang member.

“We were just baby gangsters,” Alcaraz said. That’s how one of his cousins referred to him and other kids. “We did bad things, but most of us stayed alive.”

Still, it was a rough crowd and “by the time I got through high school, I was the last male of my group that was still alive or not kicked out of school,” Alcaraz said.

That experience, along with the death of his father at around the same time, made Alcaraz’s life harder.

Fast forward to summer vacations. Alcaraz remembers when his mother would take him to Mazatlan, Sinaloa and Mexico City. The latter became a place of enlightenment, the city where Alcaraz realized the richness of his heritage.

Alcaraz recalled visiting the stunning Museo de Antropologia and touring its collections celebrating Aztec culture.

“I was told that being from Mexico was bad, but in Mexico City I would see the opposite of that,” he said.

Around the age of 16, when returning to San Diego from his vacations, Alcaraz attended free mural painting classes offered by a Chicano cultural center. He already had artistic inclinations — he comes from a family of artists — but at the cultural center he connected with Chicano artists for the first time.

“I was able to express myself, the angry energy,” he said.

He began painting murals all over — at the Centro Cultural de la Raza in San Diego’s Balboa Park, at auto shops, at Mexican restaurants. He painted images celebrating Chicano culture, sometimes cars in bright colors, but even then, he says now, his work carried political messages.

But his work isn’t liked by everyone, and neither is his attitude.

Even during his student days at San Diego State University, one of his professors told him his Caucasian classmates wondered if he was a rich Mexican from Tijuana because he could be haughty and obnoxious.

“We both laughed because he knew I was Chicano and had a lot of attitude,” the cartoonist said. “I liked to use that energy when I needed it. Not for every single thing, but to people that deserved it.”

Or, to put it another way: “I can’t help myself. I have a big mouth.”

One recent cartoon riffs off childhood nightmares. It depicts President Trump as a monster, with glowing yellow eyes, looking down on a sleeping Latino boy dreaming of graduating from college. The headline: “Good night, sleep tight, don’t let the Trump-DACA Monster bite.”

One recent cartoon riffs off childhood nightmares. It depicts President Trump as a monster, with glowing yellow eyes, looking down on a sleeping Latino boy dreaming of graduating from college. The headline: “Good night, sleep tight, don’t let the Trump-DACA Monster bite.”

His work appeals to a large audience of Latinos from different generations, but it’s also frequently targeted by people who find his cartoons edgy and offensive.

After violence erupted at a white nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Va., he drew a cartoon of Trump looking in a mirror, with the reflection bearing a little mustache reminiscent of Adolf Hitler. Trump says to himself, “Who could disavow a face like this?”

He gets hate mail from conservatives, white supremacists, anti-immigrants and even other Chicanos.

“Twitter gangsters, Facebook warriors, they all hate me, which is fine,” said Alcaraz, who acknowledges that his works brings plenty of debate to the table.

In fact, when Disney decided to make Alcaraz the consultant for “Coco,” about Miguel, a young boy who wants to be a musician, some Latinos thought it was a bad decision.

On Twitter, some Latinos charged that Alcaraz was exploiting Mexican culture to make money.

These types of criticisms appear to be in the minority, based on the feedback Alcaraz said he gets from the Latino community.

“Support comes from the old farts, from kinda the middle of the road,” he said, referring to the older generations that like his work.

Alcaraz has also seen support from younger generations.

“I like that there’s a lot of Mexican pride. You know, being woke and knowing where you’re from.”

Such is the case of Junco Canché, a 27-year-old cartoonist who has contributed for the San Diego Free Press and Pocho, a site dedicated to news and satire surrounding Latino issues.

Canché moved from Tijuana to San Diego during his early years and Alcaraz’s cartoons helped him learn and understand more about the Border Patrol, Proposition 187 and other topics.

Looking through newspapers and seeing Alcaraz’s comic strip “La Cucaracha” contributed to Canché’s understanding of his identity as a Mexican living on the border.

“I saw myself reflected in Lalo’s cartoons,” he said.

Now, thanks to television, “Coco” and social media, Alcaraz’s reach continues to grow.

“It’s like putting a mural up, but now it’s a post on Facebook or a Tweet and anyone can comment, see and share it,” Alcaraz said.

If it wasn’t for the First Amendment, however, Alcaraz thinks he might have not even had the same job that he has now. The freedom to make fun of the president and use satire to criticize the government have allowed professionals like Alcaraz to make a living.

Alcaraz has received journalism awards and recognitions by the Los Angeles Press Club and the California Chicano News Media Association.

“Technically, I’m more of an opinion person and I think that’s still being a journalist but it’s not straight reporting,” he said. “But I still chronicle and tell the truth, it’s not propaganda.”

For Elizabeth Campos, 23, journalism is as much a chance to grow as a reporter as it is to grow as a human being.

“Through storytelling, one can become a lot more humble while getting informed and informing other people,” she said.

Though Campos was born in the U.S., she spent most of her childhood in Torreón, Mexico. When she returned at 17, Campos sought to experience both worlds by comparing the two countries’ political systems and media landscapes.

Now she’s a senior at Cal State Long Beach, where she studies journalism and political science and leads her school’s NAHJ chapter.

Campos said her favorite assignment was the first video she ever filmed about an altar at a Day of the Dead event that was created for a man who died. The man was undocumented and died without medical insurance.

“It was just coming out of my comfort zone from every angle you looked at it,” Campos said. “It was a challenge of knowing how to shoot video, but also a challenge of knowing how to approach the family.”

Campos hopes to continue this kind of multimedia storytelling in her career, with an emphasis on social-media video.