DEMOCRACY IN PERIL? A Latino Reporter special project

Democracy in Peril?

A Latino Reporter special project

One person, one vote.

That has long been the fundamental ethos upon which American democracy was built. It remains, to many, the most sacred civic duty afforded to citizens of the United States. But as history has shown, this promise is not always kept, and that American commitment towards a true representative democracy remains an unfulfilled promise for some.

Recent events — ranging from widespread misinformation about the 2020 presidential election to a deadly attack on the U.S. Capitol to a wave state laws that attempt to limit mail, early in-person and even Election Day voting — have served as a reminder to many that democracy can be a fragile thing.

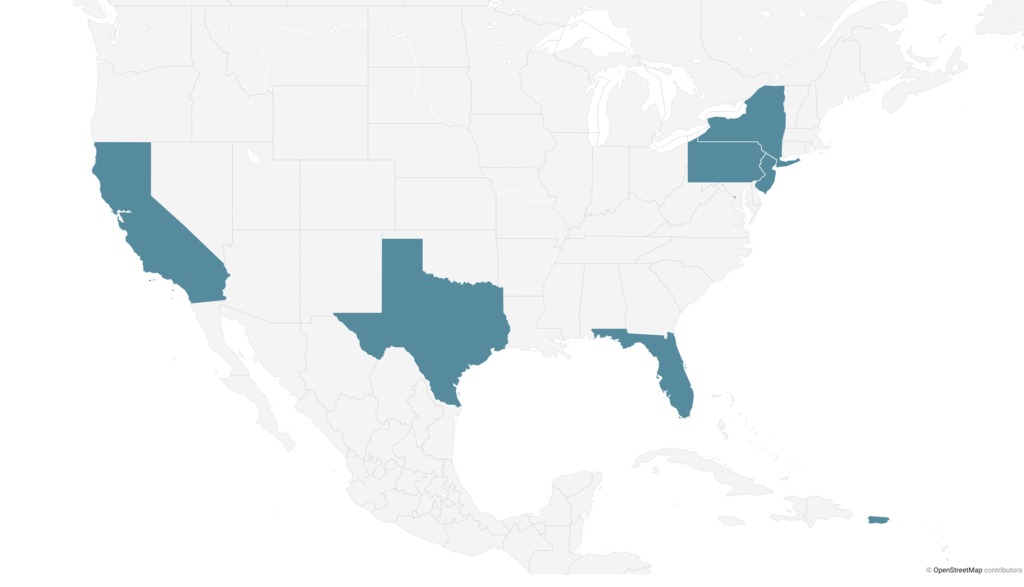

The Latino Reporter, a virtual newsroom of 12 student journalists fanned out across the country, has taken a closer look at the ways in which the United States has lived up to this promise and how the nation has faltered in fulfilling its credo of full and equal representation.

Jump to region:

Puerto Rico | Texas | California | New York/New Jersey | Pennsylvania | Washington, D.C. | International

Puerto Rico

Voting changes sow chaos, distrust among first-time voters

By Mónica Cappas & Danelys Estévez-Dávila

PUERTO RICO — Yeriel Rosario Cortés said he remembered feeling an adrenaline rush in the weeks leading up to the 2020 general election in Puerto Rico as he prepared to vote in his first election in his hometown of Bayamón.

“But after voting, I felt mixed emotions,” the 20-year-old said in Spanish. “I felt uncertainty, but I also felt confident in the candidate I voted for.”

First-time voters such as Rosario Cortés became skeptical about the electoral process in part due to changes made to Puerto Rico’s voting laws shortly before Election Day, resulting in an abrupt transition marred by controversy.

Officials amended the Electoral Code (Ley Núm. 58-2020), which regulates elections in Puerto Rico, 50 days before the primaries and five months before the 2020 election.

The amendments called for changes to the island’s voting process, such as expanding absentee and early voting eligibility, as well as extending polling-place hours in an effort to ensure greater voting accessibility.

However, the timing of these amendments raised concerns among civil rights organizations, the general population, and opposition political parties.

Critics worried that the government agency in charge of overseeing and managing Puerto Rico’s electoral process, the Comisión Estatal de Elecciones (CEE), was not going to have enough time to comply with the new law and implement the appropriate changes to guarantee the right to vote of about 3 million Puerto Ricans on the island.

Others worried the changes could potentially open the door for election fraud. For instance, a previous version of the law proposed implementing online voting in Puerto Rico, one of the Electoral Code’s most controversial amendments. But it was removed from the final version of the law following local legislative hearings.

For Rosario Cortés, constant changes to the Electoral Code during an election year felt like a disrespectful act towards Puerto Ricans. The uncertainty it caused contributed to a growing distrust towards the law, as people questioned whether or not it would fairly expand voting accessibility.

“You are counting on certain rules and you are counting on a certain protocol in the elections,” he said. “And then the Electoral Code changes abruptly in just a few days and weeks of the elections? It’s unfair for those who want things to improve.”

Mayte Bayolo-Alonzo, a lawyer with the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), agreed that part of the problem was the law’s last-minute approval and the fact that it was passed without reaching a consensus with other political parties on the island.

As the CEE moved to implement changes on such short notice, the agency botched primary elections and forced officials to reschedule voting at dozens of polling centers lacking ballots, according to Bayolo-Alonzo. The agency also faced setbacks in counting votes after Election Day, a task that lasted weeks.

“There are many factors that contributed to what happened, but the late adoption of the Electoral Code definitely had an impact,” Bayolo-Alonzo said in Spanish. “The ACLU participated as an electoral observer, and certainly some of the issues we saw, we found that the Electoral Code was to blame.”

The director of the civil law commission at the Puerto Rico Bar Association, José Lamas Rivera, told the online news publication 9 millones that changing electoral laws without political consensus can be a dangerous move for a democratic society, which contributes to a general distrust towards the government.

“They have turned this Electoral Code into a political card,” Lamas Rivera said. “That does not work in a stable society,” said Lamas Rivera.

Finding ways to empower voters

Messier Torres Feliciano, 20, said that being a first-time voter in the last election was a bittersweet experience due to poor organization and technical problems at his polling site in the town of Isabela.

“Even if you don’t want to, it makes you question the credibility of the elections,” he said in Spanish, adding that younger Puerto Ricans increasingly distrust government entities.

“I am not saying that the government is bad, nor that the government is to blame, but rushing to do things and not explaining it to the people, I think that makes people doubt,” Torres Feliciano said. “That causes problems with voting because we doubt our government due to a lack of transparency and organization.”

The same frustration and hopelessness voiced by Torres Feliciano first manifested itself in 2016 when Puerto Rico had a record low voter turnout of 55 percent — an unusual milestone for an island known for high voter turnouts between 73 percent to 89 percent.

Voter turnout in Puerto Rico’s 2020 election was also 55 percent, according to CEE.

Bayolo-Alonzo is convinced that civil organizations like the ACLU as well as community groups that stepped up to motivate disenfranchised voters to participate in the election, despite setbacks and controversies, will continue to educate people on how the Electoral Code has changed their right to vote.

While the Puerto Rican government is supposed to engage in similar efforts, and did some of that work through the CEE, community groups have been more effective in carrying out vast electoral education campaigns, Bayolo-Alonzo said.

“Many organizations recognized that here we had to help supply education with what was happening with the new Electoral Code. I do think we witnessed a nice democratic process within those efforts,” she added.

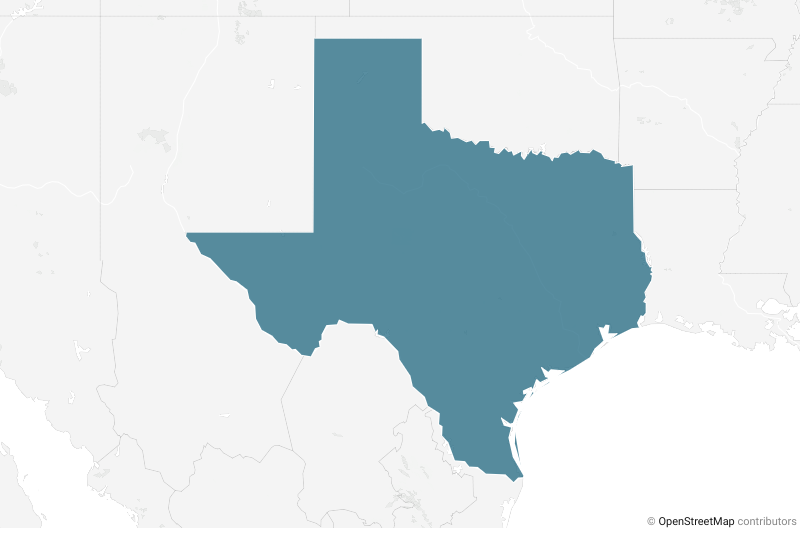

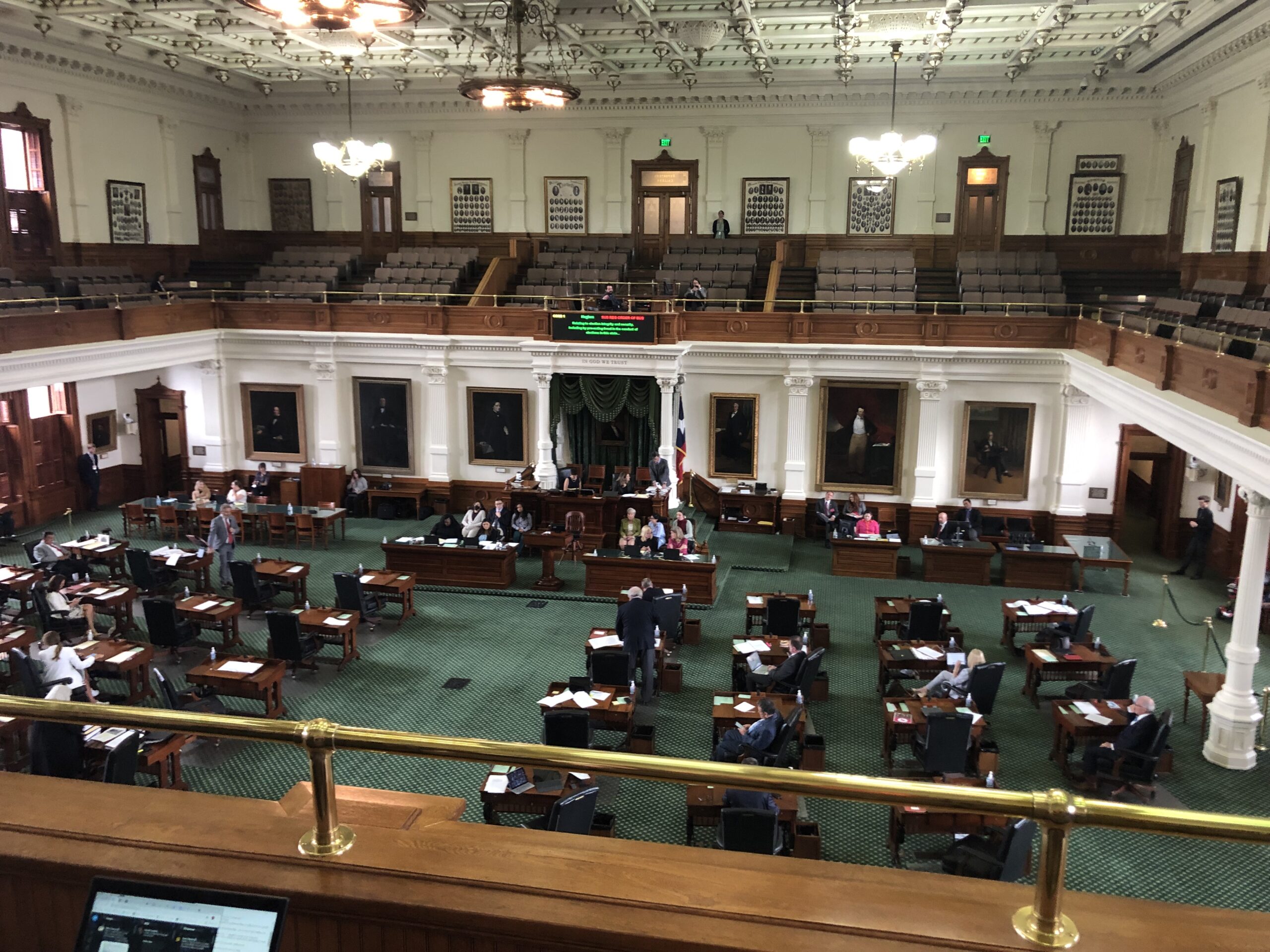

Texas

Houston woman fights for voter access at Texas Capitol

By Daisy Espinoza

BRYAN, Texas — Rita Robles is a mother, daughter and grandmother who thinks politicians don’t understand the struggles people like her face when casting a vote.

Robles, who lives in Houston, feels it’s her duty to speak up about the “discriminatory” bills that will ban drive-thru voting, 24-hour polling sites and the distribution of mail-in ballot applications in Texas. As a volunteer at the nonprofit Coalition for Environment, Equity, and Resilience, she fights for access to the ballot box.

On Tuesday, she joined community organizers with CEER and Mi Familia Vota — a civic engagement group that aims to unite Latino and immigrant communities — on a trip to the Texas Capitol to show support for House Democrats who left the state the day before to prevent Republicans from voting on bills that, in their view, would make it harder for marginalized communities to vote.

It was a rewarding experience, Robles said.

Senate Bill 1 and House Bill 3, in addition to removing drive-thru voting, 24-hour polling locations and the distribution of mail-in ballot applications, would create new ID requirements for voting by mail and establish regular U.S. citizenship checks by the secretary of state.

For blue collar workers like custodial workers, mechanics, and other voters with irregular hours, that change would make it tough to find an open polling location when they’re not busy working.

“They don’t have the time to go do that!” Robles said..

Robles speaks from experience — for 16 years, she was a secretary and administrative assistant at a law firm. She remembered that asking to leave work early to go vote was frowned upon by her supervisors and peers at her nine-to-five job.

“I was the first one in, last one out,” Robles said. “I wasn’t a lawyer or administrator. I didn’t have that privilege.”

Angelica Razo, the state director for Mi Familia Vota, said in Spanish that the proposed changes present “an attack on democracy.”

Disability rights advocates in Texas combat GOP election bills

By Marc Ray

HOUSTON — Republicans in the state are pushing for two new voting bills that disability rights advocates in the state believe are an attempt to limit voter participation. They argue the stricter voting guidelines would make the process even more difficult for people with disabilities to cast their ballots in upcoming elections.

If passed, Senate Bill 1 and House Bill 3 would impose new criminal penalties and requirements for individuals who help voters with a disability who plan to vote by mail. It would also make it a state felony for local election officials to send unsolicited mail-in ballots to voters across the state.

Both GOP bills would also require mail voting applications to be signed with ink on paper. Jeff Miller, a policy specialist at Disability Rights Texas, believes there should be an alternate way to improve voting and provide voters with the proper resources.

“We really believe that there's a way that we can write these proposals in ways that both protects the process but also allows voters with disabilities to have access to the supports that they need in order to participate in the process like everybody else," he said.

The bills would include new identification requirements for Texans who vote by mail. It would also ban drive-through voting — unless you have a disability —and tighten early voting hours.

Republicans are attempting to enforce these new guidelines as a response to allegations of voter fraud during the 2020 election. Texas Democrats believe that Republicans are making it more difficult for Texans to cast their ballots.

“There’s no democracy without the right to vote. Once again, Democrats are standing strong and united to defend the right of every eligible Texas voter to make their voice heard,” Texas Democratic Party Chair Gilberto Hinojosa said in a statement.

The Texas Election Code characterizes a disability as “a sickness or physical condition that prevents the voter from appearing at the polling place on Election Day without a likelihood of needing personal assistance or of injuring the voter’s health.”

Voters with a disability are more likely to cast their vote by mail. According to data obtained by Rutgers University, 52% of U.S. voters with a disability voted by mail before election day.

In order for a Texan's ballot to count, their signature must match on both their ballot envelope and on their application to vote by mail.

Chase Bearden, the deputy executive director of the Coalition of Texans With Disabilities, explained that votes made by people with disabilities were also affected by signature requirements.

“People with disabilities have a higher number of their votes being thrown out, ”he said. “You send your mail-in ballot [to signature verification committees] and they don’t think your signature matches the one on your application as closely as possible.”

A voter with a disability is allowed to obtain assistance from someone they trust to fill out their ballot, but must include the person's name and address next to their signature. The person helping must also add their signature.

In response to the controversial bills, Texas lawmakers traveled to Washington, D.C., this past week in an attempt to stall the new GOP election bill process.

Advocates battle indifference in rural El Paso communities

By Brandy Ruiz

SPARKS, Texas — Nestled between Interstate 10 and the city of Horizon is Del Rey Fruit Stand, a locally owned grocery store where stacks of fresh salsas, candy, and frozen bolis pack shelves as customers stroll past a panaderia and an aisle filled entirely with chicharrónes and chips.

The shop, which locals call “la fruteria” or “El Del Rey” is the heart of Sparks, an unincorporated Mexican-American community in El Paso County. Residents here can’t vote in any of the local city council and mayoral races — they can only cast ballots in county races. And although El Paso County has, over the years, boosted voter access, community organizers say many of its residents are politically disengaged.

It’s one of many places in Texas where democracy falls out of reach for Latinos.

Aaron Alvarez, 23, for instance, doesn’t care if he gets a say in city races.

“One vote doesn't make a difference,” Alvarez said. “If I had a choice to vote, I’ll vote. But it wouldn't matter at the end of the day. It’s your vote against like 1,000 people or more — millions of people in the world.”

Rocío Fierro-Pérez, a political coordinator for the Texas Freedom Network, said that many people in the area share that attitude.

“When you make it harder for people to go vote, they're gonna be like ‘Well, nothing's going to change anyway, and I can't take the day off of work because I can't even afford my rent,’” Fierro-Pérez said. “‘I can't afford to take care of my kids to put food on the table, to keep the lights on.’”

On July 13, the Texas Senate passed legislation that would make it harder to cast a ballot by baning drive-thru voting and 24-hour polling stations, prohibiting election workers from sending mail-in ballot applications to voters who did not previously request them, and instating monthly citizenship. House Democrats fled the state to prevent a vote in that chamber.

Alejandra Gonzalez, a 36-year-old Jehova’s Witness, said the changes would not impact her life because she willingly doesn’t vote. Her attitude illustrates the challenges civic engagement advocates come up against in communities like hers.

“As a Jehova’s Witness, we don’t support any government because as Christians we support what Jesus promised us one day: That he would be the one to fix the world,” Gonzalez said. “He will solve the world’s problems.”

Fierro-Pérez emphasized that the key to encouraging civic engagement is education and said that through her nonprofit, she hopes to achieve that.

California

California restores voting rights to formerly incarcerated

By Laura Anaya-Morga and Jorge Flores

CALIFORNIA — Residents in the country's most populous state restored in November the voting rights to more than 50,000 people on parole. The passage of Proposition 17 was championed by organizations advocating for the rights of formerly incarcerated and disenfranchised individuals. The change, which was approved with a majority 60% vote, allows those reentering society to register to vote automatically.

Proposition 17’s proponents relied on arguments surrounding the effects of the prison system on marginalized communities of color. According to the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, as reported by the Los Angeles Times, three out of four men leaving California prisons are Black, Latino, or Asian American. Those communities have disproportionately been denied the right to vote.

A report by the California Initiative Review on Prop. 17 highlighted that while Black people made up 6% of the state's adult population in 2016, they made up 26% of the state’s parole population. Numbers for the Latino community also show an imbalance. According to the Prison Policy Initiative, Latinos were 38% of the state's population in 2018, yet made up 41% of those incarcerated.

The majority of states already restore voting rights to people formerly incarcerated, according to the National Council of State Legislature. And in the District of Columbia, Maine and Vermont, people formerly incarcerated never lose their right to vote. Eleven states, however, revoke voting rights indefinitely or require a governor's pardon to restore them. Proposition 17’s victory is an addition to a trend of democratic states on the west coast making voting easier.

The restoration of voting rights is a concern for advocacy organizations, such as The Sentencing Project (TSP), which has provided research since 1986, with priorities on protecting voter eligibility and full civic inclusion. In 2016, TSP published “Six Million Lost Voters,” a state-by-state breakdown of disenfranchisement of people who were convicted in the past.

Keeda Haynes, state campaign strategist of The Sentencing Project, explains how the group has been a catalyst for political change in the country.

“What we are doing is stripping people of their political powers,” Haynes said. “(TSP is) pushing forward the right of vote in the political process. We do a lot of advocacy work.”

Before joining TSP, Haynes spent four years in prison for a crime she claims she did not commit. Haynes experienced first-hand being stripped of her right to vote.

“When I came home (after spending years in prison), I couldn’t immediately vote, so while the country was celebrating, voting for the first black President, I wasn’t able to vote for him,” Haynes said. “We are excluded from participating in decision-making.”

After completing her sentence, Haynes attended and earned her law degree at Nashville School of Law. In 2020 she ran for Congress to represent Tennessee's 5th Congressional District. Even though she lost against incumbent Jim Cooper, a Democrat, her campaign elevated the conversation about restoring voting rights in the state.

Shortly after defeat, she joined TSP to continue advocating for the restoration of voting rights for people formerly incarcerated, allowing her to expand her work to a national level. She began her new role at a time of heightened political distrust fueled mostly by Republican politicians.

Unlike California, some western Republican-led states, such as Arizona, proposed bills that would further restrict voting options. Policymakers and legislators in California, however, made proposals to simplify the voting process and end voter suppression by expanding access to the polls. It was in this environment that Proposition 17 won.

“We know that California is a very progressive state and tends to be aggressive moving forward,” Haynes said.

“Voting has become very political,” said Gregory Chris Brown, associate professor of criminology at California State University, Fullerton and chapter president of the California Faculty Association, which supports restoring voting rights to people formerly incarcerated. “There’s always been this fear that if we allow criminals, who are over-represented by people of color to vote… they will vote Democrat. There are certain populations in California that don’t want people to vote.”

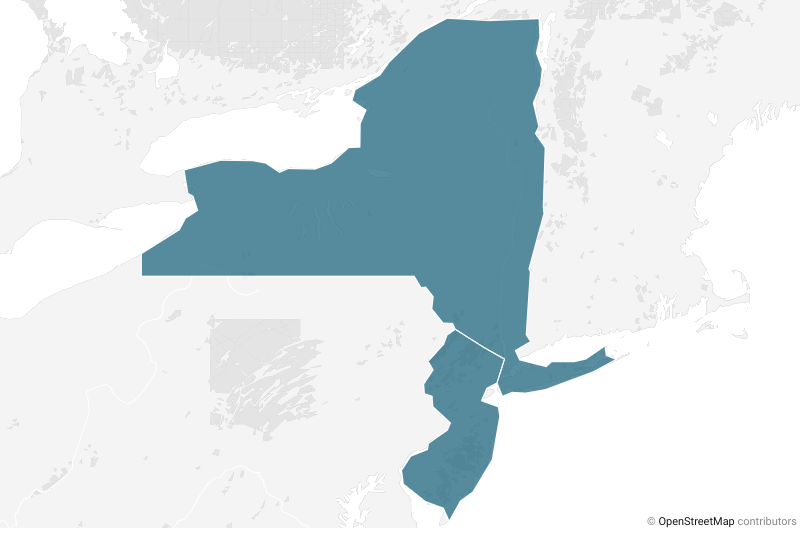

New York / New Jersey

Polling resource allocation on Long Island highlights inequities

By Maya Brown

FREEPORT, N.Y. — Last November, more than 55,000 voters cast ballots in the first two days of early voting in Long Island. Higher turnout meant longer lines, but some were longer than others. In Freeport, N.Y., an estimated 200 people waited in line to select their presidential candidate. Some even brought chairs so they could sit as the hours passed.

The line outside the Freeport Recreation Center wrapped around two blocks. Some people got tired of waiting for hours on their feet and left. Higher voter turnout or short polling hours are just a few things that can result in long lines. In Freeport, where about 42% of residents are Hispanic and 29% are Black, other factors contribute to these realities.

Gentrification, voter suppression and the allocation of polling resources all contribute to issues voters can run into at the polls, according to the Brennan Center for Justice. The center, a nonprofit public policy institute affiliated with New York University Law School, has found that voting machines, poll workers, and poll books can all make a big difference.

Areas with the longest lines typically have the fewest machines, poll workers, or both, according to research published by the center in 2014. Areas with higher percentages of voters of color tend to have fewer machines, researchers found. As a result, that's where the longest waits tend to be.

The study underscores the contrast between Freeport and Merrick, N.Y., a census-designated place where about 88% of residents identify as white. While Freeport voters waited an estimated three hours to enter the polls, community members in Merrick said it took them about half an hour. Freeport residents shared their experiences in a Facebook group.

The Nassau County Board of Elections did not respond to an email requesting information about how elections officials allocated resources at polling places in Freeport and Merrick.

Aaron Scherb, the director of legislative affairs at Common Cause, a nonpartisan grassroots organization, explained that election officials have broad discretion when it comes to allocating polling resources.

“In some localities, we see very various tactics which, often racist driven local elections officials, [try] to make it harder for certain communities to cast their ballot,” he said. He added that's reason for uniform national standards to ensure every vote gets counted.

Push to increase Latino engagement in upcoming New Jersey elections

By Denisse Quintanilla

HIGHSTOWN, N.J. — Latino advocacy groups in New Jersey aim to engage 100,000 Latino voters for the state’s upcoming election. They hope the state’s response to the pandemic, which has had devastating effects on the Hispanic community, will draw them to the polls.

According to the COVID Tracking Project, Latinos made up nearly a fifth of all COVID deaths in New Jersey. Data from a Gothamist analysis showed 361 men and 76 women between the ages of 18-49 died due to COVID-19 complications.

“A majority of our community died compared to other communities because of what historically has been issues that haven’t been addressed,” said Javier Robles, executive vice president of The Latino Action Network.

“Those issues haven’t gone away and they are issues we need to think about and address when we also think about voting for people in the future. Which one of these people is going to have the interest of the Latino community, our health and prosperity in mind,” he added.

Robles said outreach efforts got off to a slow start, but he expects things will pick up next month when social media and email campaigns ramp up. Outreach will also begin in conjunction with other organizations such as LUPE PAC, UnidosUS Action Fund and Make the Road New Jersey.

New Jersey’s primary election took place June 8. When voters return to the polls for the general election on November 2, they will elect a governor.

For the 2020 presidential election, 82% of the eligible Hispanic voting population registered to vote. About 72% actually cast ballots. It was a significant increase compared to 2016, when only 43% of registered Hispanic voters turned out.

Voter participation generally drops during primary election years, which Robles attributes to people who think they don’t need to vote because it seems like one candidate might win.

“But the reality is not that,” said Robles. “If you don’t emphasize the importance of taking half an hour to vote, making sure the person that you want with your ideas gets in, then to some extent you really haven’t done your duty as a citizen.”

When organizers with the Latino Action Network call Hispanic households, Robles says they are usually met with mostly positive responses, but some are not convinced their vote matters. Others just hang up.

Robles said his group will continue to make the case that all eligible Hispanic voters should make their voices heard in order to bring change to the Garden State.

“New Jersey has a sizable Latino population,” Robles said. “And if Latinos voted at a greater proportion than they currently do, then it would be difficult for most of the lawmakers in the state of New Jersey to get in without our vote.”

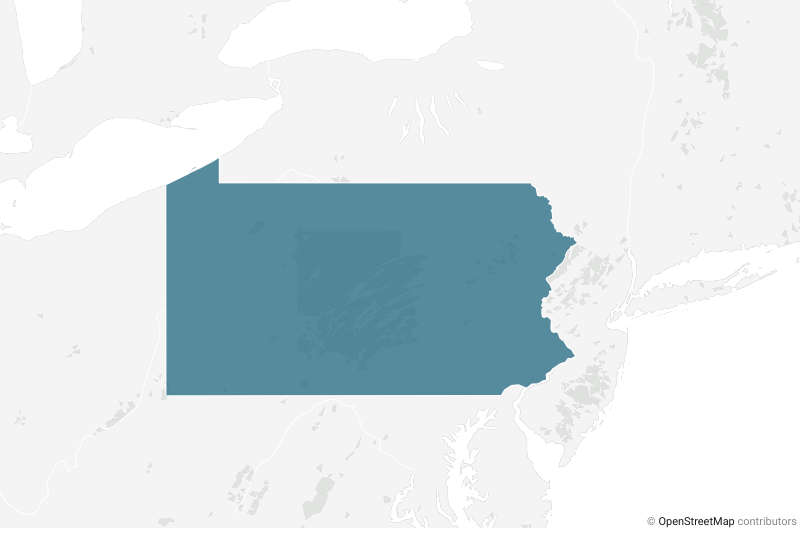

Pennsylvania

Advocates look to 2020 Census data to expand language access for voters

By María Paula Mijares Torres

[LEA ESTE ARTÍCULO EN ESPAÑOL]

PHILADELPHIA — Access to voting materials for non-English speakers who live in the state that has long been known as the birthplace of American democracy remains severely limited and difficult to navigate, activists said.

Out of Pennsylvania’s 67 counties, voters can only receive ballots in Spanish if they live in a select group of three: Philadelphia, Berks and Lehigh. If a voter speaks Mandarin or some other language, ballots are not made available to residents in any county in the state.

As the state prepares to receive new data from the 2020 U.S. Census, the first round of which is expected in August, voters’ rights advocates said they hope the demographic data will result in more counties in the state passing the federal minimum required to mandate that materials be made available in languages other than English.

“Why are you going to let language get in the way of participation? We’re talking about American citizens, so it’s important for people to maximize access to one of the most important rights that we have, which is voting,” said Will Gonzalez, the lead organizer for Ceiba, a nonprofit coalition that pushes for the economic development and financial inclusion of Latinos.

Section 203 in the Voting Rights Act, a landmark piece of federal legislation that prohibits racial discrimination in voting, guarantees that significant populations who primarily speak a language other than English can participate in the democratic process and have equal access, said Neil Makhija, a Lecturer in Law at the University of Pennsylvania Carey Law School.

But Section 203 has its limitations. The law only requires governments to take action in localities where the population reaches 10,000 or where more than 5 percent of voting-age citizens in a county are members of a single-language minority group, have depressed literacy rates, and do not speak English very well, Makhija said.

Some experts who follow the Census closely expect that Lancaster County could become the newest in the state to meet the threshold for non-English voters and Philadelphia’s mandate may be expanded to include voting materials in Mandarin.

There are more than half a million Latinos in Pennsylvania who are eligible to vote, making up about 5.3% of the electorate, according to the Pew Research Center.

The state’s Puerto Rican population makes up the largest bloc, followed by Mexicans and Dominicans. Though Latinos live across the state, the majority is concentrated in cities like Allentown, Reading, Philadelphia, and the borough of Kennett Square in Chester County.

Even with the protections guaranteed by the Voting Rights Act, advocates said, barriers for non-English speaking voters persist.

In 2019, voting machines in Philadelphia were displaying information in Spanish, but the printed receipt that confirmed voters’ selections still came out in English, said Gonzalez. This meant that voters could not confirm that their selections were correct.

Groups like Ceiba have also advocated faster distribution of Spanish-language information by Philadelphia ahead of elections to better explain the process.

Although mail-in ballots are available in Spanish in the entire state, Gonzalez’s team had to work with the Department of State to make sure that the electronic request to receive a ballot could be done in Spanish as well for the 2020 elections. Before this, the process could only be done in Spanish if you printed the form online and mailed it — a barrier for many low-income Latino families.

“That required people to have a computer to download it, have a printer with toner to print it, fill it physically, put it in an envelope and mail it, and many Latino families saw that as an additional expense because they don’t have all of those requirements accessible,” Gonzalez said.

Nonprofits like Ceiba are filling gaps in the government response.

They organized panels to spread information about Section 203 and lobbied state officials and commissioners. They created their own materials in Spanish to teach communities how to correctly vote through mail.

Gonzalez said that voter turnout among Latinos in the last election still was not enough.

“They don’t want to vote because they don’t think they can make a difference,” he said.

Other factors are also at play: the state’s Latino population tends to be poorer than the average voter, and lower-income voters are generally more likely to hold jobs with inflexible hours that make voting harder.

Over the last year, Latinos have also suffered economically amid the coronavirus pandemic. Pew found that 59% of Latino families reported losing jobs or income due to the coronavirus earlier last year.

Washington, D.C.

Odds are stacked against them, but D.C. statehood advocates won't give up

By Olivia Montes

Washington, D.C. — For Vietnam War veteran Hector Rodriguez, the fight for D.C. statehood runs deep.

Rodriguez is one of nearly 30,000 servicemen and women who live in the nation’s capital, where, although they have dedicated their lives to defending the democracy of the United States, they do not get an equal say in its governance. He founded the organization Veterans United for D.C. Statehood to represent the interests of those, like him, who have experienced the pain of combat and war, but feel as though the “deepest wound comes from our own people” as the federal government continues to deny equal representation to District residents.

“As a soldier on the killing fields of war sent by the U.S., we fought with our lives,” he said. But when they returned, “We were denied rights as citizens.”

Residents of the District of Columbia are not represented by voting members of Congress. The government that oversees the federal city is subject to federal oversight, meaning members of Congress from far-flung states can leverage their power to influence social and legal policy in the District, and, in some cases, overrule the city’s own citizens.

The fight to make D.C. the 51st state made historic strides over the past year as a bill supporting its incorporation was passed by the House of Representatives in a 216-208 party-line vote. The bill, fittingly named H.R. 51, now awaits its fate in the U.S. Senate.

To pass, the bill needs 60 yes votes in the Senate from members of both the Republican and Democrat parties. This reality has sewn doubt even among statehood’s most fierce supporters.

Former president and founder of the D.C. Latino Caucus Franklin Garcia, who served as one of the District’s so-called shadow senators who lobby Congress for full enfranchisement, said hope for D.C. rests on getting rid of the filibuster.

“Our fear right now is that I don’t know that there is consensus within the Democratic caucus,” Garcia said. “Not all Democrats in the Senate have signed up to our statehood bill. … We’re just not clear if the leadership in place right now is going to decide to push for that vote.”

As of May 1, the bill had garnered the support of 46 Senate Democrats, as well as President Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris. But, Garcia added, the lack of bipartisan support will complicate the road to making D.C. the 51st state.

Many Senate Republicans have argued that allowing D.C. to formally join the union as its own state could lead to the dismantling of the separation of powers and the national capital, as well as unfairly granting a voice to one individual city.

Del. Eleanor Holmes Norton, the District’s non-voting member of Congress, said she is “encouraged” to see the issue catching on more widely than it has in the past among Democrats and the public at large.

“I have every reason to believe that D.C. will achieve statehood,” Norton said. “It takes time to become a state -- all states have taken time.”

According to statistics provided by the pro-statehood advocacy group 51 for 51, the District of Columbia has an estimated 712,000 voting-age residents, which is more than the voting populations of Wyoming or Vermont. D.C. is also home to large Black and Latino populations, with 46 percent of residents in the District identifying as Black and 11 percent as Hispanic, according to U.S. Census data.

Garcia emphasized the connection between D.C.’s lack of statehood and the continued marginalization of Black and Latino communities.

“We have our own flag, our own music — there’s this entity, the essence of the city right now that needs to become something that is unique to us,” he said. “The lack of representation has been an outcry for people leaving the District of Columbia for a very, very, very long time.”

According to data collected by the D.C. government following a referendum on the 2016 ballot, 86% of residents support D.C. becoming the 51st state.

“I’m encouraged by the progress President Biden is making on bills before the House,” Norton said. “And that will move us closer to statehood, among other things.”

But as each day passes, and the statehood bill sits untouched in the Senate, even statehood’s fiercest advocates have begun to grow frustrated. But, Garcia said, not resigned.

“We’re never going to give up; we’re going to come back again, and again, and again. We hope that most of us are not going to die not seeing the day when D.C. becomes a state. This is something that will not go away.”

The world

Mi esquinita del mundo: An international student considers U.S. politics

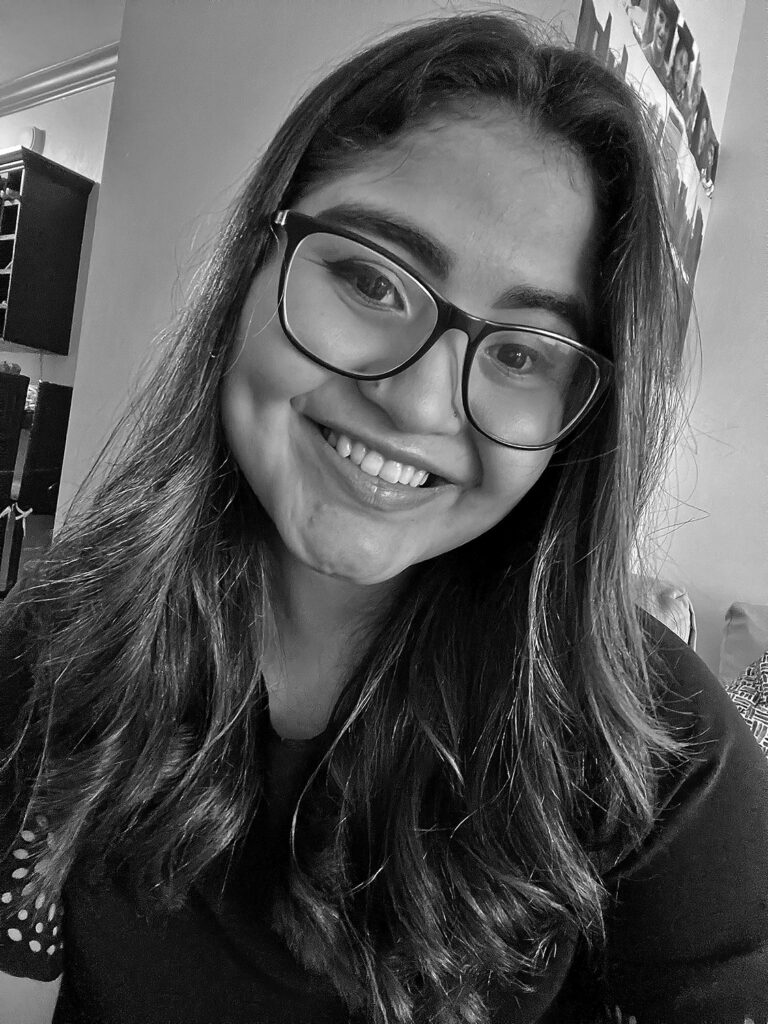

By Aurora Martínez

NICARAGUA — Understanding politics from an American perspective has been one of my biggest challenges as a Nicaraguan studying in the United States.

I have had countless debates with my friends — mostly people born and raised in Latin American countries — who grew up with many different ideologies that are all imperfect.

Sometimes it’s an Argentinian friend expressing admiration for the socialist policies of former Bolivian president Evo Morales. Other times, a Venezuelan friend will criticize their own country’s oppressive regime.

In my home country, older Nicaraguans tend to see the world without nuance. For many of them, political ideologies in the United States are drawn explicitly down party lines: Democrats support socialism, communism and misery, while Republicans uphold conservatism, capitalism, a free market and a successful society.

People often fail to see good and bad qualities from both sides of the spectrum, failing to place the sanctity of human life above all else.

I have similarly been perplexed by the American impulse to use Cuba’s protest movement to project opposition to the U.S. embargo on Cuba. Even the Black Lives Matter Global Network Foundation, which aims to make the world a fairer place for marginalized people, got it wrong.

The organization issued a statement saying that the unrest resulted from the “U.S. federal government’s inhumane treatments of Cubans.” It urged America to lift the embargo, which it claims is being used to punish Cuba for its “commitment to sovereignty and self-determination.”

As history professor Jorge Felipe Gonzalez wrote in a piece for The Atlantic Saturday, “the organization is overlooking what has triggered the events — Cuba’s systemic denial of rights to its people, poor material conditions, lack of social mobility and the inequality that plagues all Cubans, but disproportionately Afro-Cubans, who are at the forefront of the widespread demonstrations.”

[Related: “Black Lives Matter Misses the Point About Cuba,” The Atlantic]

Many of my Cuban friends have fled the island not because of an embargo, but out of a desperate need to live with freedom and dignity.

These experiences have taught me it’s hard to put clearly defined parameters on ideologies.

America’s relationship to international politics is much more complex than many people, both in my home country and in the United States, seem to think.

The Latino Reporter is an annual publication put out by a staff of student and professional journalists selected to participate in the National Association of Hispanic Journalists student project, which coincides with the organization's yearly conference. Learn more about this year's participants here.